Welcome to the sixth and final part of Czapp’s course on freight.

In the first episode we looked at the different ways that cargo can be moved through supply chains around the world.

In the second, we looked at the different participants in the drybulk freight market.

In the third we looked at the ships themselves.

In the fourth we looked at the contracts needed to move goods. In the fifth we looked at cost control.

- Types of Freight

- Drybulk Ocean Freight: Who Does What?

- Drybulk Vessels, Cargoes and Routes

- Drybulk Freight Contracts

- Freight Costs and Price Risk Management

- Container Freight

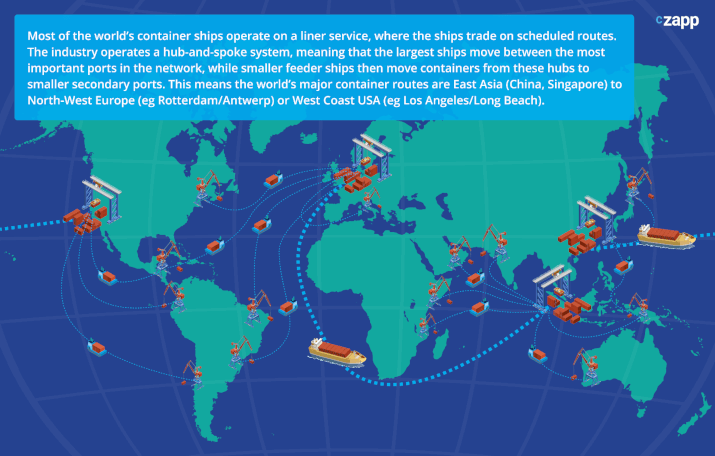

Now for something a bit different. Up to this point we’ve focussed primarily on the drybulk market. But many of the concepts also apply to the container market too.

Containers: The Basics

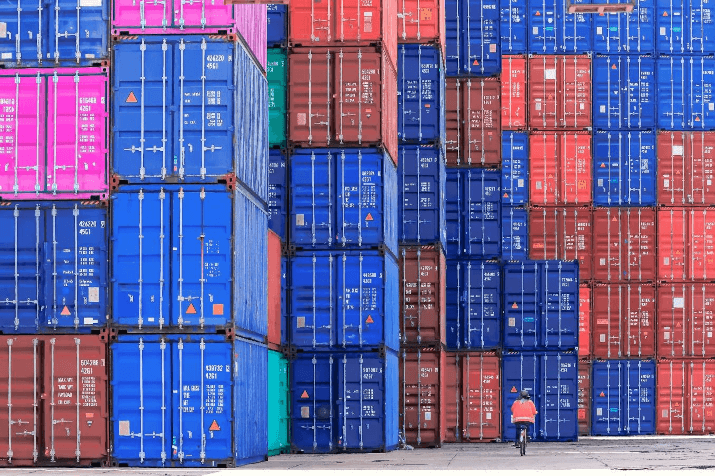

Container ships are cargo ships that carry all of their load in truck-size intermodal containers.

Source: Shutterstock

They are a common means of commercial intermodal freight transport and now carry most seagoing non-bulk cargo. The ships have storage areas which are divided into cells using rails to load the containers onto (these can be seen on the image of the vessel above).

Container ship capacity is measured in twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU), but a typical container ship is usually loaded with a mix of 20-foot and 40-foot ISO (International Organization for Standardization) containers (again, see image above).

Source: Shutterstock

40-foot containers are the primary container size, accounting for more than 90% of all container shipping. Containers are 8ft wide and usually 8 feet 6 inches high or 9 feet 6 inches high (known as high-cube containers; see image above for the two different height containers in a stack). The containers are usually made of corrugated, rust-retardant steel with a plywood floor and have lockable doors fitted at one end.

Source: Shutterstock

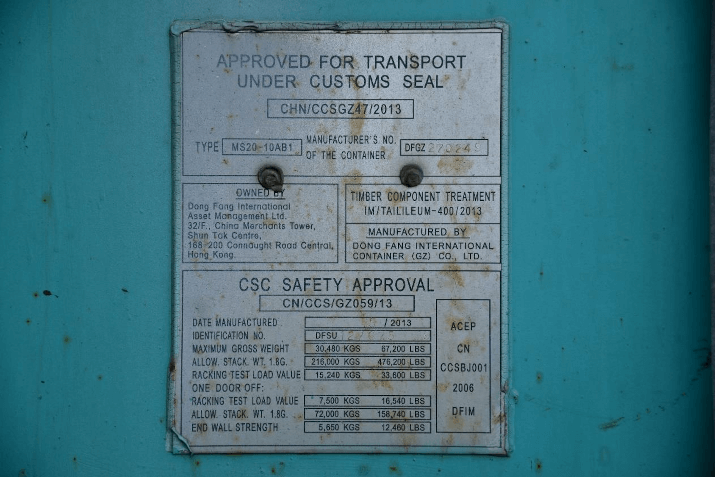

Every container travelling internationally is fitted with a safety-approval plate which shows the container’s age, registration number, dimension, weight, strength and stacking capability. Each container is allocated a standardised reporting mark 4 letters long followed by 6 digits and a check digit to allow identification and tracking. The codes are issued by the Bureau International des Containers (BIC).

Source: Shutterstock

Container doors are usually sealed so that tampering is evident.

Containers have castings with openings for twistlock fasteners at each of the 8 corners, allowing for the box to be gripped from above, below or the side and to enable safe stacking. See for example the image below where a container is being lifted by a crane at the port using the upper twistlock fasteners.

Source: Shutterstock

Vessels are loaded according to a stowage plan. This contains 3 dimensions; rows, tiers and container slots. rows run bow to stern and are numbered from the middle of the ship outwards, even numbers on the portside and odd numbers on the starboard side. Bays run across the ship and are numbered from bow to stern. Tier shows the height within a stack, numbered from bottom to top. Ensuring optimal stowage for vessel stability and speed of loading/unloading at port is essential and fully computerised.

There are several types depending on their required function. Most of the world’s container fleet are general purpose containers designed to carry dry goods. Other prominent types include refrigerated containers and tanks in frame, which can ship bulk liquids.

Containers: The Benefits

Before the advent of containerization in the 1950s, break-bulk items were loaded, lashed, unlashed and unloaded from the ship one piece at a time.

Source: Shutterstock

The first modern container ship voyage was in 1956, and the first purpose built fully cellular container ship was commissioned in 1964. From this time the use of containers has revolutionised world trade.

By grouping cargo in containers, each cargo is moved once and each container is secured to the ship once in a standardized way. Containers are designed to be transferred from and to ships, trucks and trains without accessing the cargo and so can be carried by several modes of transport in one voyage. This means a container ship can be loaded and unloaded in a fraction of the time it takes to unload the same cargo from a bulk vessel.

Source: Shutterstock

Loading and unloading takes place by crane, not manual labour, further cutting costs. Containerisation also resulted in less breakage of goods and theft. The speed and lower expense of moving goods in containers has enabled factories to operate on-time guaranteed delivery and just-in-time manufacturing, reducing their inventory expense.

Containers: Logistics

Shippers load cargoes into containers that are provided by the shipping lines.

Source: Shutterstock

These are then delivered to docks by rail and/or road for loading onto container ships by cranes. When the ship’s hull has been fully loaded, further containers are stacked on the deck.

Container movements aren’t limited to loaded containers. Empty containers also need to be moved back to where they are needed.

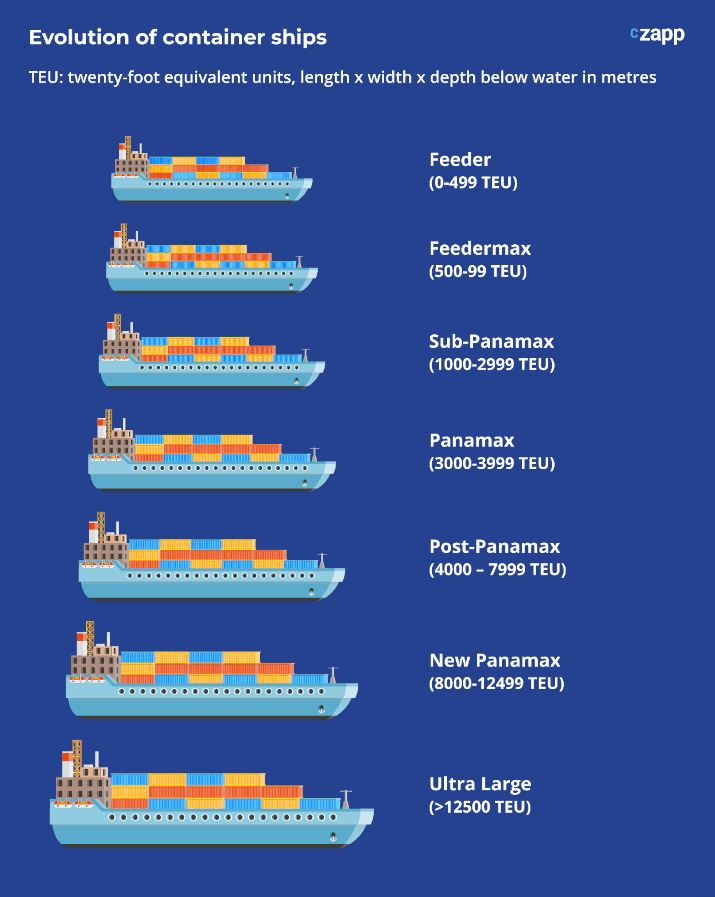

Economies of scale means that there’s been an upward trend in container ship size through the years to reduce costs. Container ships are distinguished into 7 major size categories: feeder, feedermax, sub-panamax, Panamax, Post-Panamax, New Panamax and ultra-large. The main limitations today on ship size are the ability of ports and terminals equipped with cranes able to handle ultra-large ships and the dimensions of the world’s main waterways.

Companies have further controlled costs and maximised their utilisation rates through slot-exchanges, vessel-sharing agreements and co-operative agreements. There are now 3 main container alliances which control more than 90% of the world’s dominant trade routes.

Ocean Alliance: CMA CGM, COSCO Shipping Lines, Evergreen

THE Alliance: Hapag-Lloyd, HMM Co Ltd., Ocean Network Express, Yang Ming

2M Alliance: Maersk Line, MSC

The lines remain operationally independent and are not allowed to collude on freight rates or capacity.

In times of container scarcity, container rates rise. In times of container oversupply, rates fall. Container lines can respond to overcapacity by slowing their ship’s speed, cancelling port calls (also known as blank sailings) or laying up ships.

CZ works with customers to help manage container freight price risk. Prices of the liner routes can be mutually agreed ahead of time (much like the FFAs in the previous episode), enabling an extra control on input costs. Please contact Max or Richard for more details.

Losses

Containers are extremely robust and can be stored and transported without being inspected for months at a time. Only when corrosion is extensive is there a risk that the twistlock fixings fail or the container cannot be safely moved.

Source: WK Webster

However, hundreds of containers are lost at sea each year, sometimes through broken fastenings, sometimes through poor loading and sometimes through vessel sinkings or groundings. As container ships get larger and their load stacking become higher, the risk of containers falling into the sea increases as the rolling of the vessel on rough seas can create high torque at the top of a container stack, breaking lashings and locks within the stack. Once in the ocean containers fill with water and will frequently sink.

Other Uses

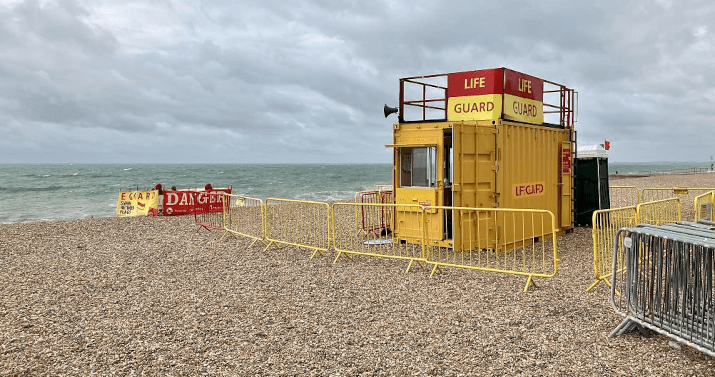

Permanent placement of containers around the world for storage is common. In some parts of the UK containers have been repurposed as lifeguard stations on beaches.

Containers have also been used in cities to block protests, as stages for political rallies, as mobile or modular homes, as cafes and as computer data centres. [link https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-magazine-monitor-28901576]

Source: Shutterstock

Problems

The strength of the container – that the cargo doesn’t need to be disturbed during its entire voyage – is also a weakness. Containers can be used to smuggle contraband without interference. The majority of containers are never inspected due to the sheer numbers that are moved.

Czapp Explains – Freight series: Types of Freight