Opinion Focus

- The price of freight has dropped as much as 40% since its 2021 highs.

- This has been caused mainly by demand concerns related to a potential recession.

- But longer-term fundamentals suggest freight prices will rebound due to supply issues.

Global supply chain disruption has driven the price of freight up since the COVID-19 pandemic swept the world in 2020. Now, as prices drop, there are suggestions that freight costs have been inflated and are now rebalancing. But fundamentals in the longer term indicate higher prices are here to stay.

Freight Prices Drop

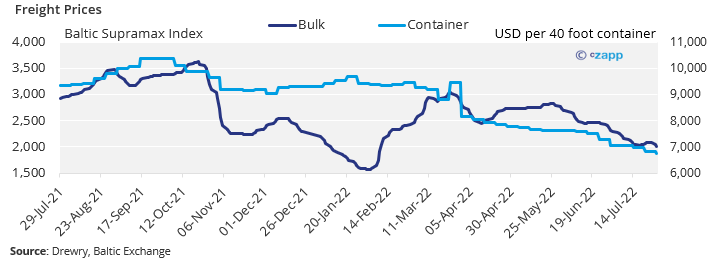

After a prolonged rise, freight rates have recently fallen back sharply. The Baltic Supramax Index measures price fluctuations in vessels with the capacity of between 50,000 and 60,000 dead weight tonnes (DWT). The index is down just over 40% from its October 2021 highs.

The drop in freight rates can be placed squarely on the shoulders of two factors: a lack of demand from China due to ongoing lockdowns and nervousness over a potential global recession.

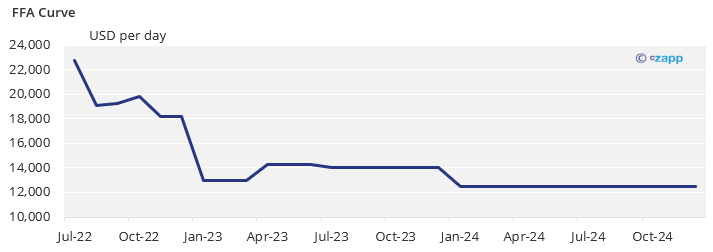

The freight market tends to be very sentiment driven. This is because the daily hire rate is dictated by an openly traded over-the-counter market called Forward Freight Agreements, or FFAs.

Shipowners will use FFAs to decide how much to charge for freight in the future. If FFAs are expensive at the point the voyage will be made, the freight price will also be expensive.

In turn, pricing of FFAs is based on future supply and demand dynamics for freight.

IMO Rules Complicate Market

With a lack of demand from China and the risk of a global recession, it would be reasonable to assume that freight prices will continue dropping. But that may not necessarily be the case.

Despite weak demand, there are issues on the horizon that could restrict vessel supply and ultimately push up prices again.

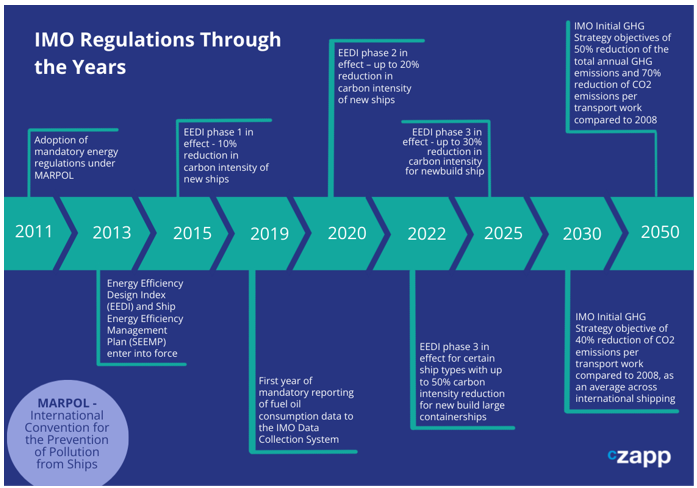

The primary concern on the mind of shipowners are new environmental rules coming into force. The shipping industry is overseen by the International Marine Organization (IMO). Since 2011, the IMO has set out various requirements for vessels with the aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from shipping by 50% and CO2 by 70% by 2050.

These measures are mandatory and mean ships need to slash their emissions. But there is uncertainty over the best way to do this. Some older ships can be retrofitted to bring emissions down, while about 40% of the world’s new ship orders will be able to run on lower-polluting fuel, according to Clarkson’s Research.

But it is worth mentioning that IMO 2020 served as a lesson to many shipowners. This legislation required that ships use fuels with minimal sulphur content and many owners were forced to retrofit vessels, clean tanks or fit scrubbers, which can remove harmful elements from exhaust gases.

This proved costly and complex for shipowners. An analysis by UNCTAD found that the switch to low-sulphur fuels resulted in fuel costs almost doubling across grain and oilseed routes. That meant nominal voyage rates increased by about USD 5-30/tonne.

As a result, most ship owners have opted to wait for further clarity on new rules, while dropping cruising speeds. According to Danish Ship Finance, a 10% drop in cruising speed can reduce fuel usage by up to 30%.

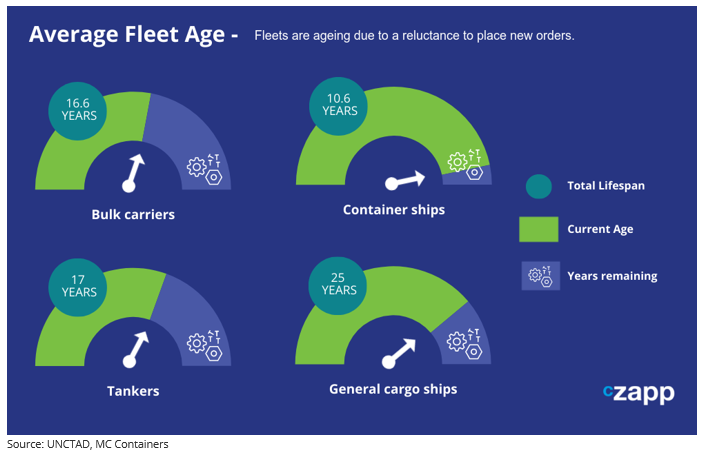

The effects of this are twofold. Firstly, cargoes take longer to get to their destinations, meaning there is less capacity on a global level than it would first appear. Secondly, the fleets are ageing due to a reluctance to place new orders.

Long Term Fundamentals Bullish

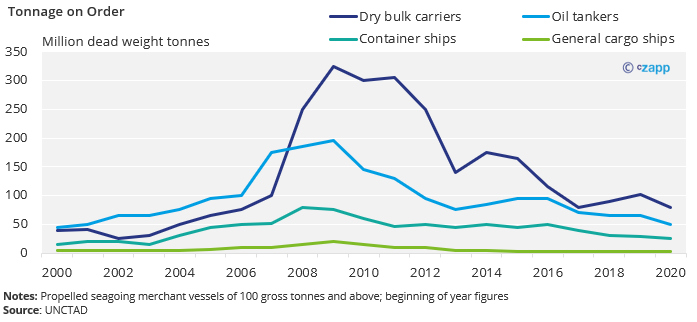

Demand is low at the moment, but supply is expected to be extremely constrained in the future. While the global fleet is expected to grow over the next few years, new orders are a drop in the ocean compared with those from 2007 to 2009.

Of course, this period led to a massive oversupply of the shipping industry, causing prices to flatline over the next 10 years or so. However, there are two major differences today that contrast to 2007.

Firstly, due to the IMO rules, there is a real risk that much of today’s global fleet will soon become obsolete – or will require costly retrofits; and due to a lack of clarity over the new rules, there is currently a reluctance to order more ships.

Secondly, access to freight finance is much more difficult to obtain than it was 15 years ago. This means there is less willingness to lend – primarily due to IMO uncertainty – which is also hampering global fleet growth.

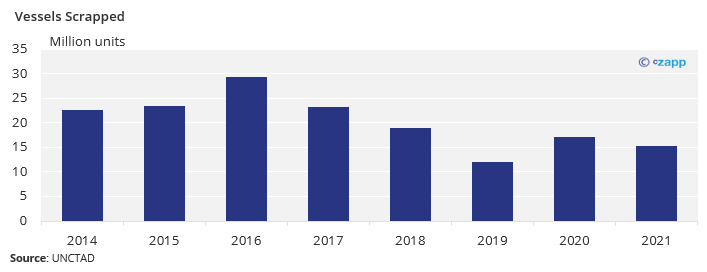

As well as lack of growth, the shipping industry is facing the prospect of having to scrap older ships. If rates continue to fall, companies may well look to scrap less efficient vessels.

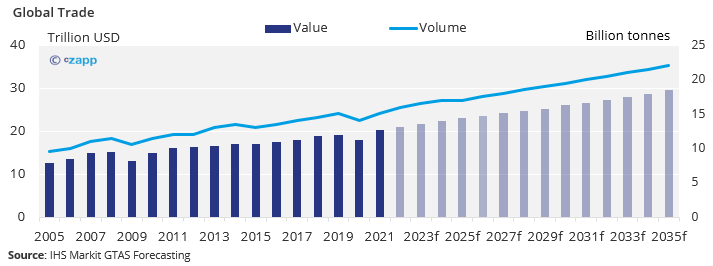

Although demand is deemed low, global seaborne trade is still expected to grow by 2.65% on average each year. This creates a potentially huge imbalance between supply and demand.

Oil Price Adds Another Layer

The price of fuel is one of the biggest costs for shipping companies, given that it can make up about 50-60% of total operating costs.

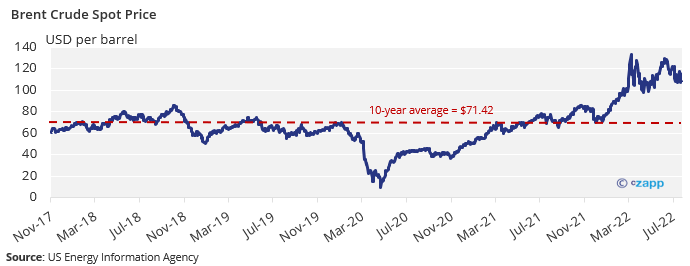

The cost of oil remains elevated at over USD 100 a barrel. In contrast, the average price over the previous 10 years was USD 71.42.

The price of oil has continued to rise despite the threat of a global recession, which would ultimately lead to demand destruction. This is because there is tight supply and no real prospect of a significant increase in production.

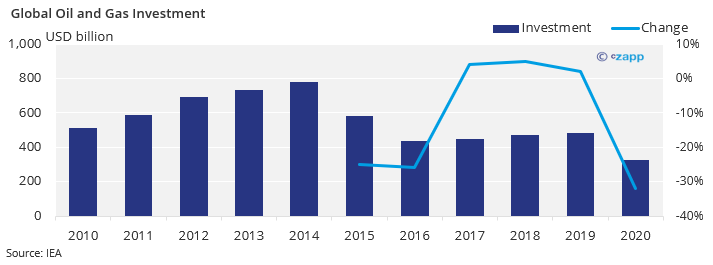

Since 2014, investment in oil and gas supply has been stagnating. According to the International Energy Agency, this investment dropped 25% from 2014 to 2015, and then proceeded to fall a further 26% in 2016. Ever since, there has been no significant recovery. After years of under-investment, there is no prospect of the taps being turned on any time soon.

Despite high prices, there has been no indication of a decline in demand, according to analysts. The IEA says global oil demand is expected to grow by just shy of 1 million barrels a day every year to 2025.

According to McKinsey, the world must bring online another 38 million barrels a day in production capacity by 2040 to meet global demand in a business-as-usual scenario.

All this indicates that oil prices will continue to rise unless there can be an accelerated transition to alternative energy sources. In the end, this could mean higher long-term freight prices.

Concluding Thoughts

So, what does all this mean?

Well, the demand-side risk of a global recession is largely counterbalanced by longer-term supply-side uncertainty stemming from IMO rules. This means freight prices are unlikely to fall again to pre-pandemic levels.

For companies that depend on freight, it is possible to take advantage of all this information to save on costs.

If you’d like to know more about how Czarnikow can help you manage your freight risk, please contact Rosi Koleva on rkoleva@czarnikow.com.

Other Insights that may be of interest

Why Demurrage is Bolstering Inflation

Green Shipping Starts to Make Waves

Interactive Data Reports that may be of interest …

Consecana Panel

CS Brazil Weather Update