Opinion Focus

- In WEF’s latest Global Risks Report, it identifies climate change as one of the most severe threats faced by the world – and one to which we are ill equipped to respond.

- The global food supply chain has been trying to map and reduce its emissions in recent years.

- But as world leaders meet in Davos this week, Czapp asks whether or not we are considering the right factors and making the right changes.

Climate change is perhaps the biggest threat to global prosperity. And our food systems are a massive contributor to the climate imbalances we are seeing more and more of nowadays. But how can we be sure that we are taking the right action to address the climate crisis?

Curbing Food Emissions Becomes Crucial

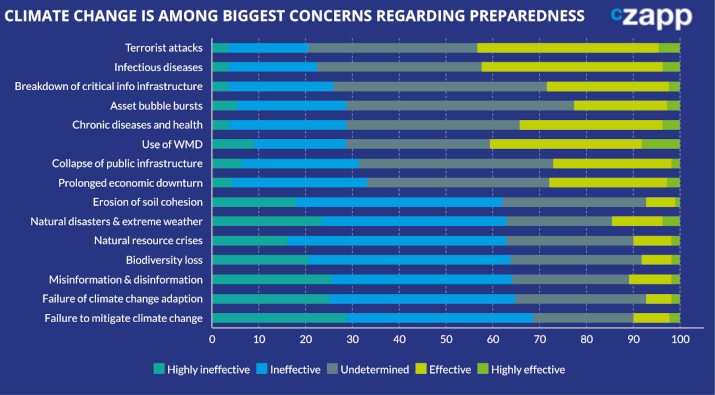

Ahead of the Davos Summit kicking off this week in Switzerland, the World Economic Forum released its annual Global Risks Report. In it, climate change failures and natural resource crises were among the greatest areas of concern.

Source: World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2023

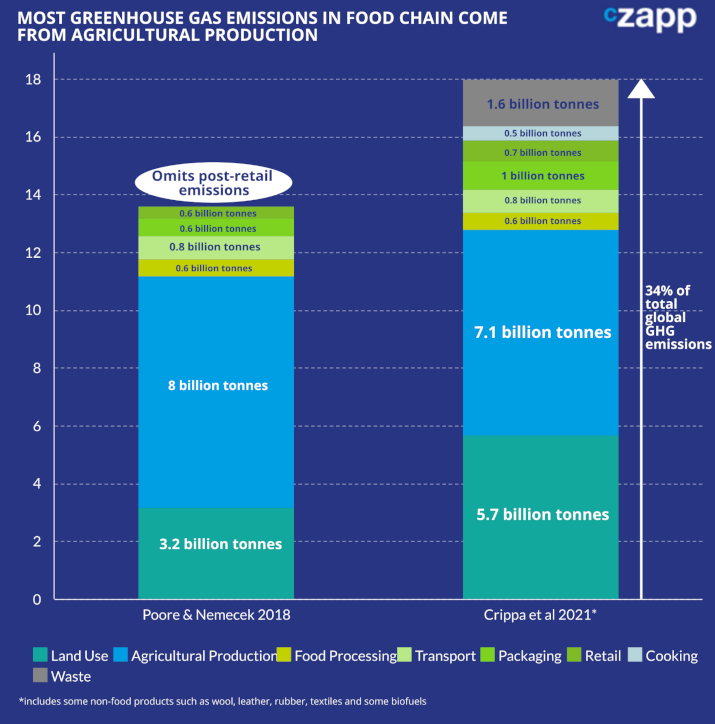

Our food systems are a crucial facet of the wider environmental discussion. It is estimated that about 25% to 30% of the world’s total emissions come from the food system, while one third comes from the agricultural sector as a whole.

Source: Our World in Data

This is why addressing emissions across our food systems is so important, and why it will be one of the issues at the top of the agenda at this year’s forum.

Tools Help Us Quantify Emissions

It can be hard for the general public to understand the emissions produced by the behemoth global food system. But there are a variety of tools now available that break down the emissions that belong to each product.

- The BBC has created an emissions calculator based on data from Oxford University research.

- MyEmissions has built a calculator using primary data from clients and secondary data from studies – information that is constantly evolving.

- Greenswapp is an app that allows shoppers to scan barcodes in supermarkets and compare the impact of each product so that they can shop in a more environmentally friendly way.

- The Capture app allows consumers to map not only their food emissions but also their day to day transportation emissions. But the measuring system is much more generalised than other systems.

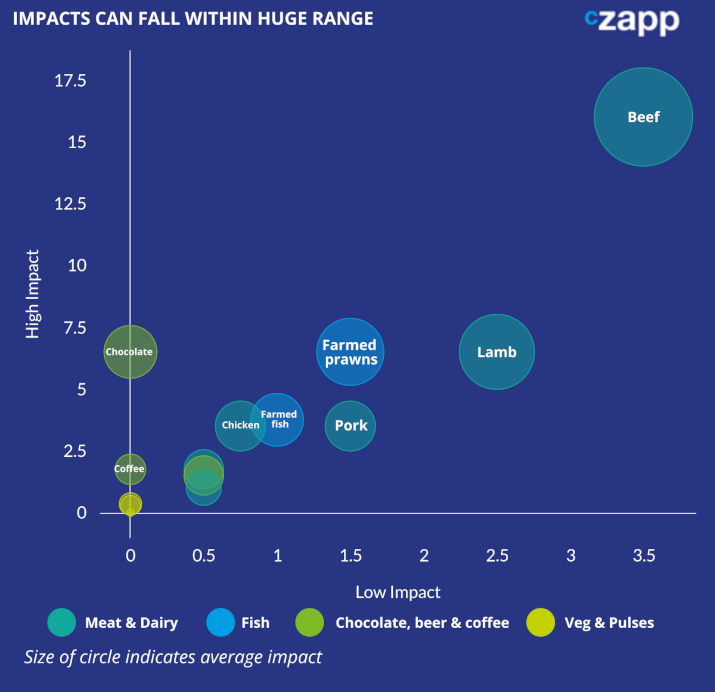

All of these apps are helpful in providing a general idea of emissions, but no single version is fool proof. For instance, some of the ranges calculated by the studies are very large. This means we could be hugely underestimating our impacts.

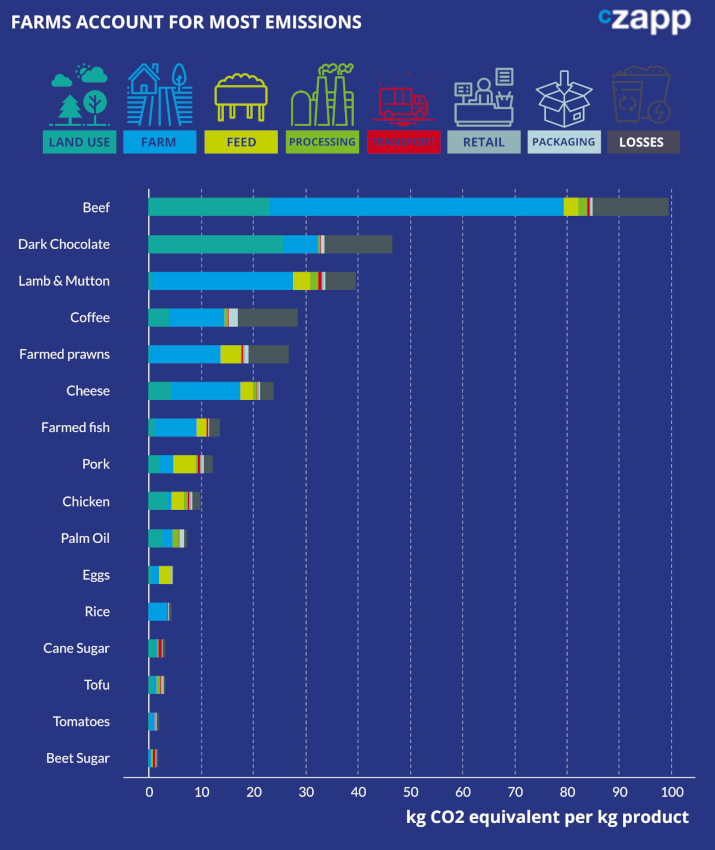

Source: Poore & Nemecek, 2018

So, we would need to understand the exact origin, growing conditions, inputs and water use on that particular farm to really know how many emissions a certain product produces.

Carbon Offsets Provide Incentive

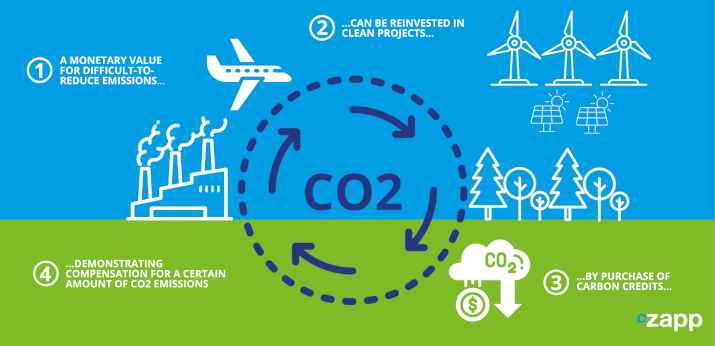

Reducing carbon impacts can sometimes feel impossible, so an interim solution has been to use systems such as carbon credits to allow companies and consumers to offset emissions.

For example, if company A must import palm oil from Indonesia in order to manufacture a certain product, the impacts can be at least partially offset through its reforesting efforts in Borneo.

While this is generally recognised as a stopgap solution, there are several criticisms. One of these is the idea that the wealthy can essentially pay to pollute.

But a whole market has been developed around carbon, allowing more transparency in its pricing. The idea is that, as fewer allowances are provided, the cost will rise, making the purchase of carbon unviable and incentivising emissions reduction.

The market is still young and – importantly – voluntary. Until now, a powerful regulator to oversee the market has not emerged.

But encouragingly, there are many initiatives across various countries to adopt carbon credits. In India, a stabilisation fund is reportedly being planned to sustain carbon prices, while Singapore recently passed a bill stipulating a minimum carbon tax of SGD 25 (USD 18) per tonne.

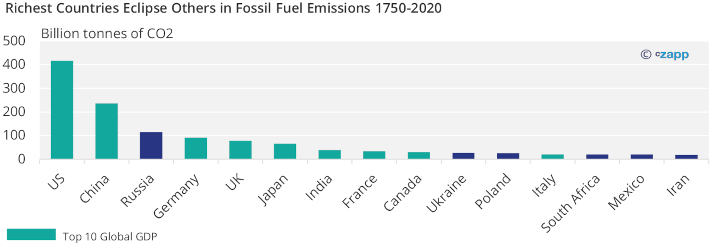

Some initiatives focus on incentivising carbon reduction in the developing world by providing cash in return for reduced carbon emissions. But according to the Global Carbon Project, it is the world’s wealthier countries that are overwhelmingly responsible for CO2 emissions.

Source: Global Carbon Project

Are We Mapping the Right Things?

This brings us to the question of whether our priorities are right as we try to get to grips with emissions.

There are three stages that are generally considered in measuring food emissions: the agricultural phase, including any impacts from land use change, the processing-to-retail phase and the post-retail phase.

But what about feedstocks for meat or fertilisers for crops? When we calculate the emissions of a chicken breast for example, should we also take into account the entire lifecycle of the corn that fed that chicken? It is easy to see how this could soon spiral out of control.

There’s also almost always a trade-off.

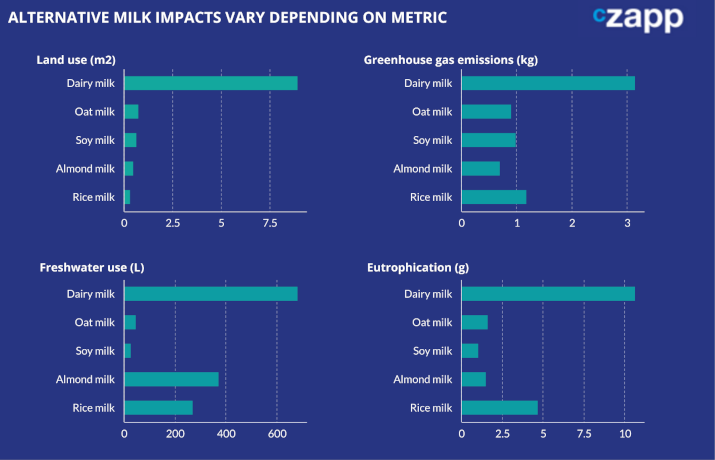

For instance, plant-based milk is generally better for the environment than traditional cow’s milk. But while some use very little land, they require large amounts of freshwater or other inputs.

Source: Our World in Data

Food Mile Mapping Isn’t Always the Answer… Or Is It?

One way that emissions can be measured is by considering food miles – the distance food has travelled and its resulting transportation emissions.

In theory, the rise of globalisation and trade should mean that transportation accounts for a decent chunk of food systems emissions. But transportation emissions are minimal, according to most estimates.

So, since the farm and land use stages contribute the most to emissions, this should mean that the type of food we eat is far more important than where it comes from. In short, it should theoretically be far less polluting for a European to eat tofu made from Brazilian soybeans than a steak from down the road.

But it’s not quite that black and white. In a new study published in Nature Food, researchers found that we could be grossly underestimating transportation-related emissions, which could mean trade of goods could play a much larger role than previously thought.

This could mean that maybe the steak is the better option.

And that’s also where emissions reduction efforts clash with elements of food security. If transportation does contribute minimal amounts of emissions, it would be easy for any country to give up farming altogether and import all of its food.

But of course, that would also compromise biodiversity, soil quality, and nutritional diversity. Some countries would have an outsize responsibility to feed the global population, while others would see their food autonomy jeopardised.

And famously, every country is only a few missed meals away from revolution.

Concluding Thoughts

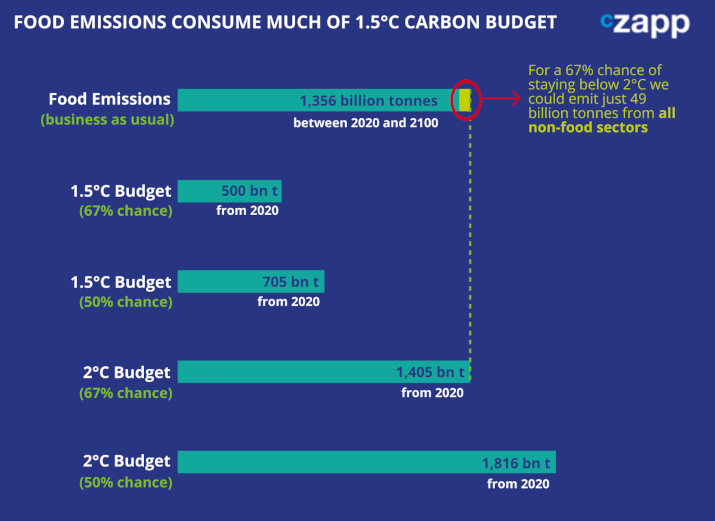

So, what does this all mean? Well first of all, measuring and trying to minimise our emissions is important, not least because food emissions alone could push the world beyond the 1.5-degree global temperature change target.

Source: Our World in Data

And while there are various ways of measuring emissions, all methodologies have one thing in common – they are imperfect.

There are swathes of compelling, yet conflicting evidence, so how do we cut through the noise? Ultimately, the main factor that matters is engagement.

We may not be entirely accurate, and we may not be looking in the right place, but the important thing is that we are looking. Keeping attention focused on the impacts of our food systems is the biggest contribution we can make to mitigate climate change.

So download an app and give emissions tracking a go. It might just surprise you.