Insight Focus

- Escalating food and fuel prices have caused widescale rioting in Sudan.

- Sudan will have issues with food security as fertiliser, grains prices continue to rise.

- Widescale stockpiling could begin globally

Sudan is in the grips of a crisis. Added to fuel and grains shortages, the country’s wheat production is down by one third on the year. The rising burden of fertilisers will have implications for the next crop. As other countries look at Sudan’s situation, there’s a risk that widescale stockpiling could begin in an effort to shore up enough food for a “just in case” scenario. Developed countries will likely find it easier to stockpile, given the infrastructure required for grains storage.

Sudan Reaches Crisis Point

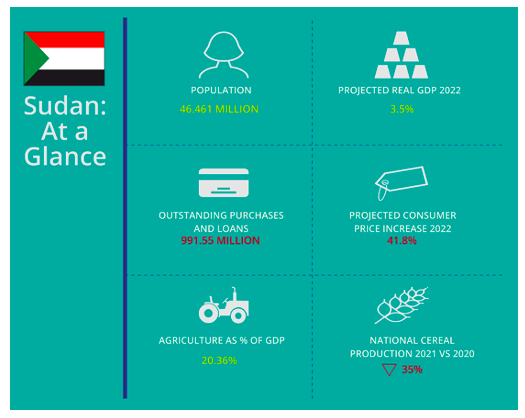

In Sudan, acute levels of food insecurity have prevailed for many years. As of May 2021, according to the International Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), 7.3 million people are in high levels of food insecurity and require urgent action. The situation was predicted to deteriorate due to impacts of “the lean season, tribal conflicts, diminished labour opportunities causing low purchasing power, high food prices as well as inflation.”

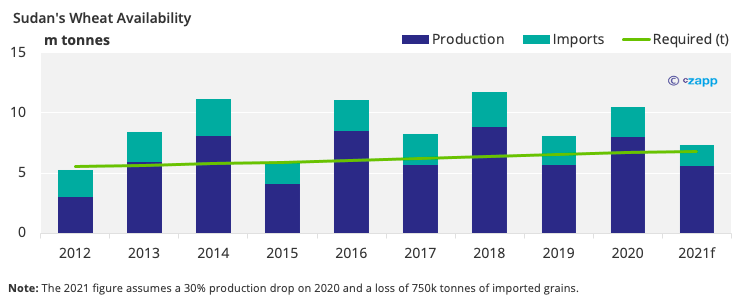

A recent special report by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization highlighted that national cereal production levels to March 2022 are down 35% on the previous year and 30% lower than the five-year average. Sorghum production is 32% lower and wheat production is down 13% year on year. Cereals, particularly sorghum, are the main staple food in the Sudanese diet.

“The drop in yields is expected to result in high food prices and that could have severe impact during the usual hunger season between May and October,” a spokesperson from the UN World Food Programme told Czapp. The hunger season is the period when food supplies have been depleted with several months still remaining before the next harvest.

Pest, disease and weeds were much more prevalent during the crop year due to higher costs of pesticides and rains were irregular over 2021 with dry spells interspersed with heavy flooding. Pasture conditions have deteriorated over the prior year and there’s a shortage of animal vaccines due to high costs.

Political Turmoil Drives Economic Collapse

The overthrow of President Omar al-Bashir in 2019 after 30 years in power sparked the beginning of massive political upheaval in Sudan. The transitional government that was installed after the coup earned the support of the international community, with billions of dollars being awarded in loans and grants. But in October 2021, the government was arrested during a military coup.

A brief period of turmoil followed in which the Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok was imprisoned, then released and re-instated before resigning. Military general Abdel Fattah al-Burhan retains control of the country. This has led to widescale protests and political unrest throughout the first three months of 2022.

Although the current food supply concerns are not caused directly by the conflict, structural issues such as high inflation and the availability of foreign currency is exacerbating the situation.

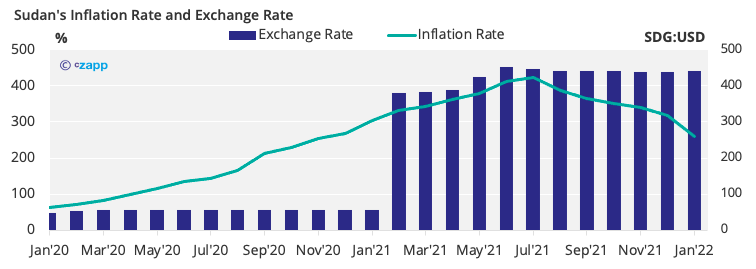

Sudan’s inflation rate has risen steadily over 2020 and 2021 because of continuous currency devaluation. Fuel subsidies were also withdrawn, causing energy prices to soar. Many farmers are now unable to afford critical inputs.

“The rising food prices and food insecurity is expected to put further strain on the capacity of the government to address the needs of the Sudanese population,” says the WFP.

Export Market Squeezed by Russia, Ukraine

FAO data shows that Sudan’s grains consumption reached 7.6m tonnes in 2019. About 2.5m tonnes of this was imported. Trade data shows that Russia and Ukraine combined export around 750k tonnes of grains per year to Sudan. With a harvest that’s down by around 30% and the loss of almost 10% of its supply from Eastern Europe, the consequences could be disastrous for Sudan.

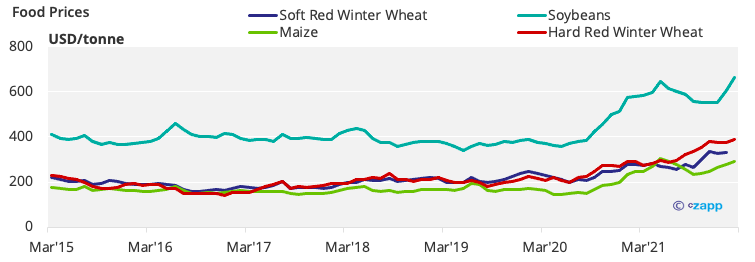

The WFP says that those who rely on the market to purchase food will be the hardest hit. As of mid-March, the cost of imported wheat to Sudan increased to USD 550 per tonne, up 180% on the year. In the same period, the Sudanese pound was devalued by about 19%, going to 447 SDG:1 USD from around 375 SDG:1 USD. “The Russia-Ukraine conflict is expected to compound the rising food price in Sudan,” the spokesperson added.

Sudan’s grains production has been volatile over the years, meaning there’s been little opportunity for it to stockpile. In 2012 and 2015, for example, there wasn’t enough grains to satisfy the 152kg per capita that the population is estimated to consume. In 2016, 2018 and 2020, Sudan was able to meet demand with domestic production, but in the intervening years, it was at the mercy of the international markets.

Although Sudan’s wheat imports dropped in 2021, there were imports of 10 times more wheat flour than in the previous year. This is mainly because of the increasing cost of flour milling as a result of high energy costs. Imports of fruit, rice and dairy products were also higher year on year in 2021, mainly due to poor harvest conditions.

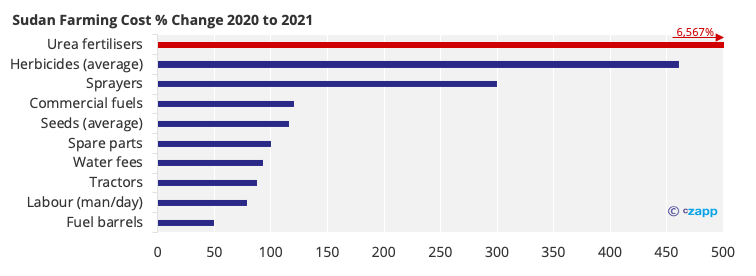

Sudan has a strong agriculture sector, with about 65% of the population involved in agriculture. The sector contributes about 20% to GDP. However, rising costs of inputs is making farming much more difficult in Sudan. The cost of fuel was up 6,500% in 2021 compared with 2020, and certain herbicides increased by about 850%.

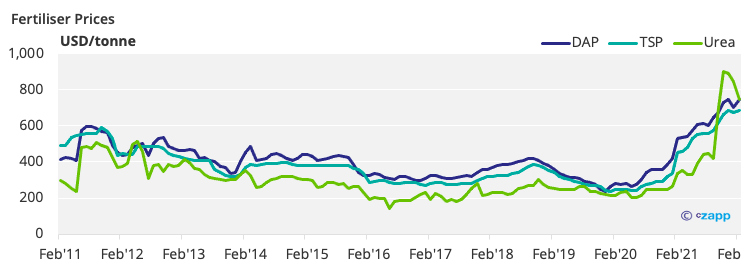

Because of higher energy prices, the cost of fertilisers has also risen. In December 2021, the price of urea reached 890 USD/tonne, up 70% year on year.

If there’s not enough fertiliser available for the upcoming crop, or the price is out of reach of Sudanese farmers, the country faces another poor harvest to exacerbate its situation.

“Lack of fertilizers and high costs of fertilizers were main challenges faced by the farmers during the past season,” said the WFP. “For the forthcoming season, given the increasing global price of fertilizers, it is likely that cost of food production will become even higher resulting in higher food prices.”

FAO Recommendations Could be Unrealistic

The FAO has issued some recommendations for the Sudanese government to “strengthen domestic production, improve food security and enhance market functioning”. Some of the recommendations include monitoring efforts, such as carrying out crop cutting surveys.

However, many of the recommendations involve substantial investment. The FAO says Sudan’s government should encourage mechanisation through an “extensive and accessible” financing programme. It also says Sudan should expand water harvesting technology and improve the country’s capacity to manufacture vaccines.

Sudan’s current economic situation means many of these investments are out of the government’s reach. In a recent debt sustainability analysis carried out by the International Monetary Fund, the agency found that Sudan is in debt distress and all stress indicators “significantly” breached the acceptable threshold. The country’s total debt is USD 56.6 billion, USD 51.9 billion of which is in arrears.

The country’s external debt is estimated at about 163% of GDP. With agriculture representative of about 20% of GDP, the current challenges will impact the government’s ability to invest. Previously an oil-rich nation, the secession of South Sudan in 2011 removed three quarters of Sudan’s oil revenues.

With no substantial source of income, high government debt and a rising cost of living, the poor harvest will likely weigh on government finances.

The FAO also encourages investment in infrastructure that would add value to the country’s exportable commodities. Oil refineries and processing plants for agricultural commodities could help the country to command higher export prices.

Private investment would be one way this could happen, although private companies would be unlikely to invest during a period of economic turmoil and continued unrest. Any investment in oil infrastructure would also require several years before it provided returns for the Sudanese government.

“WFP is very concerned about the lack of accessibility, affordability and availability of food will have on the food security and malnutrition,” said the spokesperson. “Needs are now widespread across the country, from conflict-affected areas to impoverished areas that are bearing the brunt of the economic downturn.”

Ripple Effect Could Lead to Stockpiling and More Bad Harvests

Sudan is not the only location blighted by a poor harvest. In Kenya, the worst drought in decades has dried up the soil and killed livestock. And in Ethiopia, a plague is ravaging crops and threatening food supplies.

There’s no telling how long the conflict in Ukraine could last and there’s no real information on the scale of the damage to agricultural infrastructure. This means supply constraints should continue throughout 2022, exacerbated by continued supply chain delays due to COVID lockdowns in Asia.

The real problem may arise if stockpiling begins in response to the situation in Sudan. Some countries have already taken measures to restrict exports of key agricultural goods to ensure domestic supply remains sufficient. Earlier this month, the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry added wheat products to its list of items eligible for export regulation on the 4th March. This indicates that Turkey will likely cut off these exports if domestic supply is compromised.

Both Romania and Hungary have announced a ban on wheat exports, while Bulgaria has announced plans to bolster reserves, leading many to fear an imminent export ban. Kazakhstan is already feeling the heat after Russia banned grains exports until the end of August. In Kyrgyzstan, over 90% of the wheat imports come from Kazakhstan and Russia.

As international wheat prices remain elevated at close to 400 USD/tonne, developing and low-income countries that experience problems with domestic crops will be heavily at risk of food shortages.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Egypt to Boost Wheat Production with Black Sea Disruption

Will Record Wheat Prices Incentivise Chinese Expansion?

Russia & Ukraine Grains Flows Likely to Be Disrupted into H2’22

Explainers That May Be of Interest…