Introduction

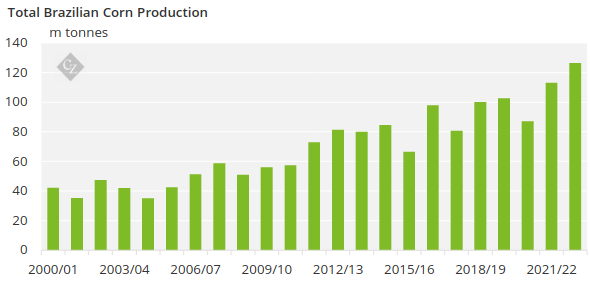

Grain production in Brazil is now responsible for more than 50% of national agribusiness. It’s therefore essential in the economy. Corn is the second most important crop in agricultural production in Brazil, behind soybeans.

At the beginning of Brazil’s history, corn was used for human nutrition. Over time, it’s gained more importance as animal feed, in addition to being strategic for national food security.

Brazilian corn is known in the market for its good quality. Brazil supplies several countries during the U.S. off-season (Brazil is the second largest exporter of corn in the world, behind only the U.S.).

Cultivation

Nowadays corn is cultivated in practically all Brazilian territory.

Even though corn is resistant to weather changes, it also needs heat and the right humidity to grow properly. The risk is that, during the flowering phase (around 65 days), the corn doesn’t find water enough to grow. This will affect the rest of the growth cycle and result in a damaged crop.

The corn planting system may vary from region to region, considering the different realities that can be found in Brazil. According to IBGE data, around 60% of corn farms in Brazil consume the grain directly on the property. Despite this, this portion represents less than 25% of national production, which highlights the great duality between the types of grain production.

While there are regions where advanced technologies are used, such as mechanization of planting, pesticide application and genetic improvement, there are also small rural properties with little or no technology and more dependence on climatic conditions.

One of the most popular planting systems is known as the no-tillage or direct drilling system. This is widely used in the central region of Brazil in the production of the second (largest) corn crop, as it allows better rotation between soybeans and corn. This system consists of planting in soils covered by plant residues, where only the place where the seeds will be placed is prepared with plowing.

This system is popular among producers as it decreases soil erosion, improves humidity concentration and the retention of soil nutrients, overall improving yields when combined with weeds and pest control. In the last decade, the use of this direct planting system in Brazilian fields has increased by more than 85%.

Brazilian Corn Crops

Corn cultivation in Brazil occurs in 2 or even 3 different harvest periods:

The weather allows Brazil to grow three corn crops. As it is a crop that requires a warmer weather, the production is linked to the spring and summer seasons. Despite this, depending on weather conditions, corn can also be grown during the winter in countries like Brazil and Mexico, where even in winter the tropical weather continues to provide ideal growing conditions.

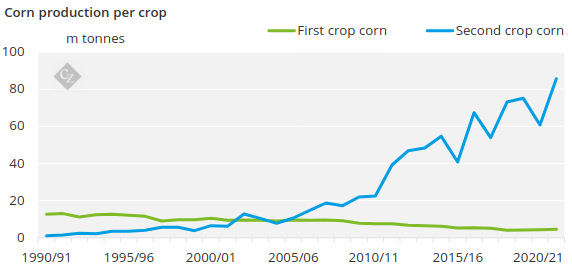

Lately, the second crop has become more important than the first crop as second corn crops can be used directly after the soybean harvest. In this way, soybean producers promote crop rotation between soy and corn, whether to increase the productivity of their land, pest control or correction of nutrients in the soil for the next season.

Source: CONAB

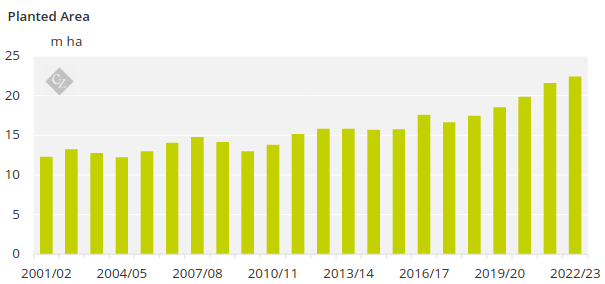

In the last five years, the area planted with corn in Brazil has increased strongly.

In addition, increased attention to crop yields has been responsible for much of the growth in production and better results in recent years.

Since 2000, corn in Brazil has generated a GDP of R$715 billion (compared to the R$7.6 trillion generated by agriculture and livestock), with more than 50% of this result being caused by productivity growth in the fields. In the last two decades, productivity has shown an average growth of about 4,2% per year.

How is it stocked?

With the increase in the productivity, Brazil has needed increasing grains storage.

One of the positive characteristics of corn (as well as soybeans and other grains) is that under the correct storage conditions – such as cleaning and drying methods to prevent insects/fungi – the grain is capable of being stored for a long period without any impact on its quality.

The main storage methods are in silos, bulk, or sacks in warehouses. Corn can be stored on the cobs in barns or warehouses in sacks; this is often done by small producers. Larger producers tend to store corn in silos.

Stocks in Silos.

Corn Production

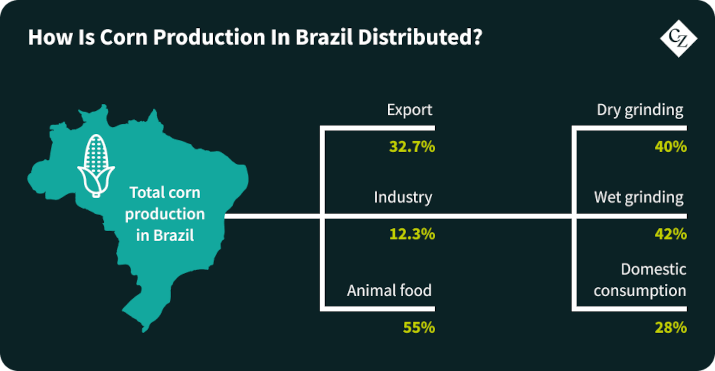

Corn is the second most produced agricultural product in Brazil, behind soybeans only. Although in the beginning it was intended mostly for domestic human consumption, corn is also now heavily used as animal feed. Thus, in less than 20 years, Brazil has gone from being a major consumer of corn to one of the largest producers and exporters (mainly with the strong development of second-crop corn, which is destined for the foreign market).

Source: CONAB

The main corn by-products are DDG (also used as animal feed, due to its high nutritional value), corn ethanol and corn oil (can also be used to enrich animal feed, in the manufacture of biofuels and industrial chemistry), in addition to products such as cornmeal, syrup, starches that are used by the food industry.

Corn ethanol Industry in Brazil

Despite being relatively new, the corn ethanol industry in Brazil has been showing rapid expansion, with large groups investing in new plants and the emergence of plants dedicated specifically to the production of ethanol.

Today, Brazil has 18 corn ethanol mills, 11 of which are flex distilleries (produces both sugarcane and corn ethanol) and 7 full distilleries (produces corn ethanol only) and are concentrated in the central-west region of Brazil, mainly in the states of Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul and Goiás.

One of the questions facing the corn ethanol industry in Brazil is its competition with sugarcane ethanol. As it is a product with a long storage life, corn allows greater consistency in ethanol production and the operation of mills.

Furthermore, while a tonne of sugarcane can produce up to 85 liters of ethanol, the same amount of corn produces between 370 and 460 liters, a significantly higher productivity. On the other hand, 1 ha of sugarcane can produce up to 80 tonnes of sugarcane while 1 ha of corn produces less than 6 tonnes. That means that more land area is needed to produce corn ethanol.

Also, sugarcane bagasse is used as a source of energy to produce ethanol, corn requires a large supply of biomass (in Brazil, wood chips are the most used for the process). Thus, while a sugarcane ethanol mill exports its produced energy, a corn ethanol mill must import it.

Exports

Brazil is the 3rd largest corn exporter worldwide, behind only the US and Argentina.

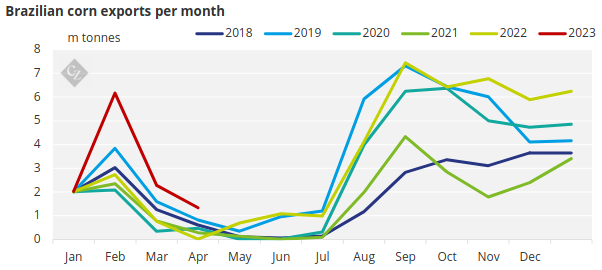

Second crop corn, also known as safrinha – or “little crop” in Portuguese – was a fitting name in the past years but this crop is now bigger than the first one in Brazil. As a result, Brazilian corn exports are now greater in the July-Dec period.

Source: Comex stat

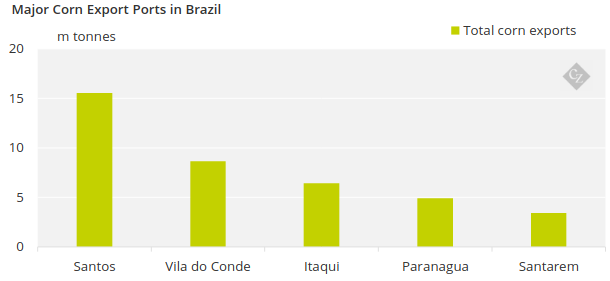

Brazilian corn is transported to ports in three ways: rail, road, and waterway.

Railways transport over 47% of corn to ports, followed by roads at 42%.

Santos is the main port for corn exports, responsible for over 1/3 of total exports (over 15 million tons per year). Aside from Santos, the other ports are mostly located in the north and northeast region (except for Paranagua Port) and are also of importance. Together, those ports are responsible for 43% of total Brazilian corn exports.

Source: Williams Lineup

Corn Price Index and Futures Market

The main corn price reference index for the physical market is the ESALQ Corn Index. It is an arithmetic average of the daily negotiated prices for the product equivalent to the base region, Campinas, Sao Paulo. The base quality of the product for the index is yellow corn, type 2 with humidity max. of 14%, impurity up to 1% on the 3mm sieve, max 6% of burned or sprouted grains and up to 12% of broken grains. The price negotiated at 162 cities are considered for the formation of the index.

Different cities that serve as a reference for price formation may have different prices according to the freight differentials and cost of production.

In general, the dollar exchange rate, freight costs and port fees, in addition to the export premium, also make a difference in corn prices in the country.

For trades using the ESALQ Index, differentials (basis) are used in relation to the base regions, defined by B3 as the physical delivery location.

As about 70% of local total production is destined for the domestic market, corn prices are more linked to domestic demand than international demand. In the futures market, however, corn traders hedge on both local and international markets, depending on the objective of the operation.

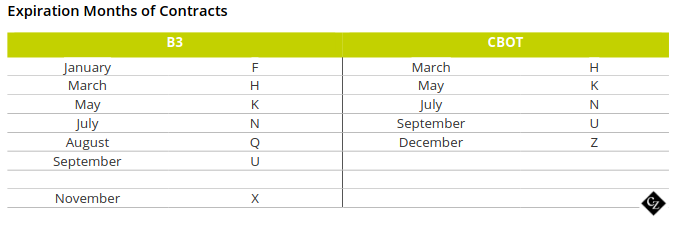

Use of futures hedging by Brazilian rural producers is still low. With grains for example, most operations in the futures market are carried out by trading companies, which negotiate in the spot market with producers and, at the other end, operate in the futures market.

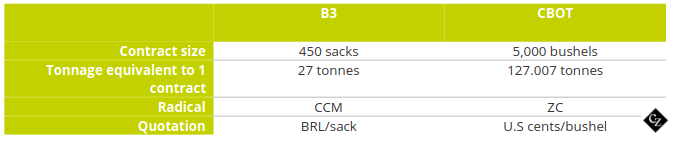

International players (trading companies in general) use the CBOT more often, as it is a world reference that will serve as a global reference of price.

Local players generally use the B3 as it has more stickiness with the domestic prices, in addition to the simplicity of not having to deal with international money remittances that eventually arises when a hedge is done on an international board of trade.