1,900 words / 9 minute reading time

- The coronavirus has now impacted all commodity markets to some degree.

- But how has wheat fared against other commodities?

- We will explore this, and the extent to which the world of wheat has changed as a result of the coronavirus, in this piece.

Wheat vs. Coronavirus

There has been no global emergency that compares to the coronavirus since the World Wars of the last century. The last pandemic of this proportion was the Spanish Influenza in 1918, which resulted in tens of millions of deaths. But the world is a very different place 100 years on.

So, what has this new deadly virus done to the world of wheat in 2020?

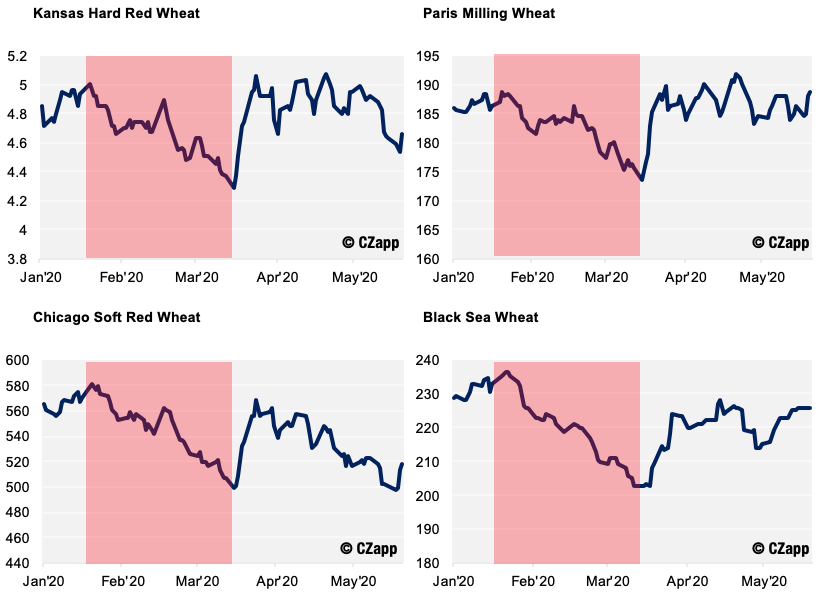

The Wheat Markets Suffered a Coronavirus-Induced Price Crash

As the coronavirus became global headline news in Jan’20, the wheat market started to feel the pinch. A ‘risk off’ mood swept through the commodity markets and gave rise to an extraordinary slump in the wheat price from the 22nd January to the 16th March.

In part, there is logic to the price crash in wheat. Economic problems tend to reduce consumer demand as people try to reduce their financial outgoings.

Markets often overreact to news, with technology allowing such easy access. This can create a herd mentality as everyone piles into the crash. Inevitably, the trade needs to stop at some point and assess the real long-term fundamentals of supply and demand.

In mid-March, the coronavirus really started to take hold of Europe, with high numbers of hospitalisations and deaths. With this, lockdowns were quickly implemented on every continent as the virus spread rapidly.

Why then, did the wheat market encounter the most extraordinary turn around? And, why at this point in time?

Quite Simply, Panic Buying…

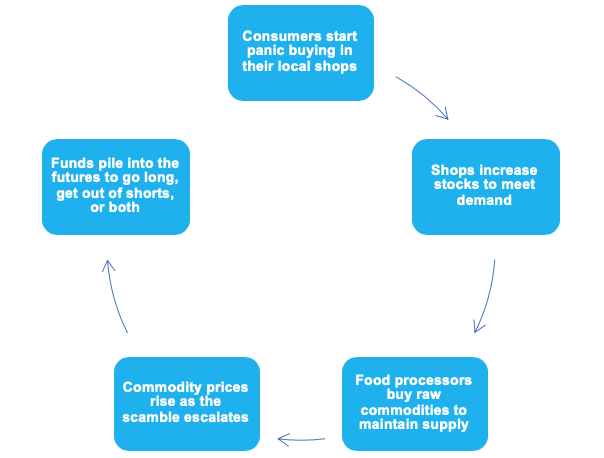

Panic buying became the new headline. This created significant short-term demand for basic foodstuffs and various wheat products; this included pasta, bread, flour, etc.

A chain reaction followed, with each step leading to the next:

This all leads to stockpiling ideas from Governments, as they begin to fear for the food security of their populations, as well as the political and social unrest this can bring.

This level of buying interest over a mere 10 days saw wheat markets regain virtually all they had lost in the previous two months of the coronavirus-induced crash.

Since late March, and through the months of April and May, the fundamentals of supply and demand have increased their focus on the wheat market, with coronavirus issues taking up less headline space.

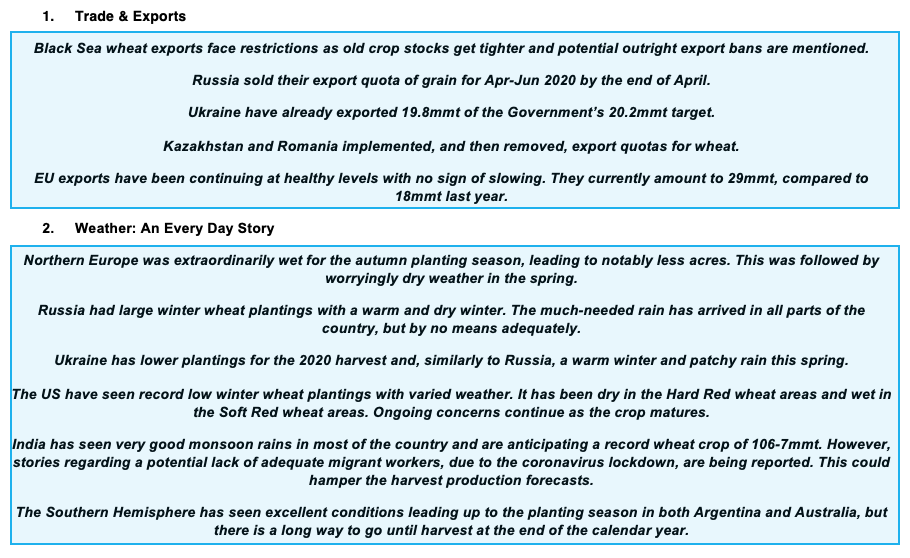

In recent weeks, the main stories have been…

Wheat vs. Other Commodities

The WHO categorising the virus as a pandemic sent shock waves through virtually all financial, commodity and grains markets. With this, prices across the board crashed from mid-January to mid-March 2020.

The volatile nature of the wheat market, as seen above, has set it apart somewhat from other financial and commodity markets.

So, we’ll now explore in more detail how the wheat market fared against these other markets.

Financials

The financials have mostly followed the long-term concerns relating to both regional and global economic health. A clear reduction in economic growth, with abundant reports of recessions unseen in the last 90 years, are common place.

A similar pattern in the drop was seen between January to March 2020 in both wheat and financials. However, any major recoveries in the financials need macro-economic changes, which will be slower and less dramatic in nature, so we have seen far fewer ups and downs, as we have with wheat over the last two months.

Oil

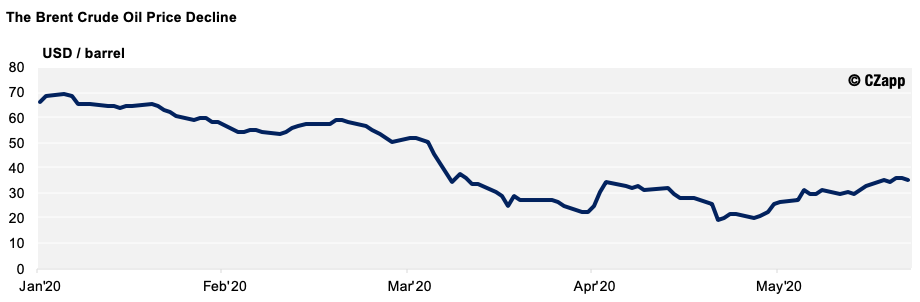

The unprecedented, and almost unbelievable, reduction in oil use around the world has been catastrophic to crude oil prices. We have even seen negative prices where storage issues have become crippling and immediate.

The reduction of air, sea, road and general industrial use of oil could not have been foreseen prior to the coronavirus outbreak. An unfortunate compounding problem for the oil price was the dispute between Russia and OPEC at the beginning of 2020, as they were unable to agree on production cuts.

As with the financials, the oil price recovery is slower and more reliant on the kick starting of industry and commerce to see significant recovery.

Metals

‘Risk off’ selling and the reduction, or even shutting down, of regional industries such as construction, manufacturing and engineering have taken their toll on metal prices. As with oil and the financials, there will need to be a longer-term resumption in these industries requiring metals before seeing anything close to pre-January 2020 levels.

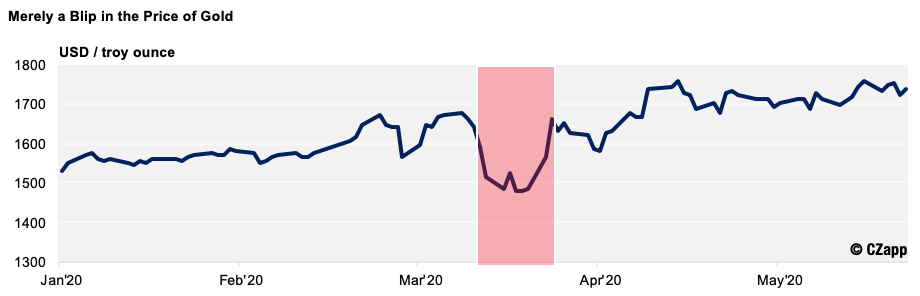

Gold

Here we have a market that sits out on its own.

A short-term dip in prices during March has been the only blip for the bull market. Given that in times of crisis, traders turn to ‘safe haven’ assets, gold can most certainly put it itself in this category in relation to the ‘coronavirus effect’. As such, it is the one that did not crash like wheat or the others.

Corn

Corn has been a fascinating market in comparison to wheat.

One could be forgiven for thinking that it would have a much closer correlation to wheat than 2020 has provided. It is, after all, used for livestock feed either as corn or DDGS. However, the collapse in the oil price has held back any rally in corn that we have seen in wheat, as a significant amount of corn is used in the production of ethanol. The reduction

in production, as plants are mothballed, has proven itself to be a heavy burden on the corn price. This, coupled with increased world production estimates and year-end stocks, provides price resistance near the lows.

Soya Beans

As with corn, soya beans are used in livestock feed. We could consider a rebound in wheat prices of help to soya bean prices, but this market has different issues to address. Most notably, the political disputes between the US as an exporter, and China as the largest importer, which have been reignited by the coronavirus.

A restoration of more normal trade flows, and the replenishing of the Chinese pig herd, may yet be needed for any real price increases.

Has the World of Wheat Changed in the Short and/or Long Term?

The wheat market has seen greater volatility than most markets in 2020 as the coronavirus has taken hold worldwide. But, fundamentally, people need to eat, so the demand for wheat will coincide with the global population size and their eating habits.

The Short Term Picture

Panic Buying: This has caused a short-term increase in wheat demand. That demand is short-lived as freezers and cupboards fill up and buying habits return to something approaching normality in the space of a few weeks. Where populations are poorer and do not have either the finances or the freezers to stockpile, this short-lived spike in demand is not significant.

Workforce Issues: There have been cases of producers and food processors reducing their output, and even shutting down, due to the lockdown, staff illness and other coronavirus-related issues. This hits short-term demand, but should, in theory, be restored once back up and running.

Eating Habits: Lockdown naturally reduces the amount people are eating out. This has an impact on what people eat, as well as how much they eat. Financial worries impact what people eat, with staple products, such as bread, seeing more demand than meat, for instance. This has a profound effect on an individual’s wheat consumption.

The Longer Term Picture

Lockdowns and Quarantines: These have caused migrant worker issues in many parts of the world. Many people in the supply chain, from producers to retailers, can need varying degrees of migrant workers. Restricted movement, due to lockdowns and coronavirus safety concerns, will make 2020 a difficult year for many.

Government Action: Egypt is looking to increase wheat stocks as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. They have looked to change the way they purchase wheat from FOB (loaded at port of origin) to CIF (delivered in boat to destination port). Much of this relates to logistics and food security concerns for the world’s largest wheat importer.

A lack of food security, as history has shown over centuries, is socially and politically unacceptable and has been the cause of many government overthrows and civil unrest.

Logistical Issues: In Russia, there were reports of lorry drivers being unable to deliver to the ports without strict coronavirus-related paperwork. In South America, concerns over seafarers potentially transmitting coronavirus when in port are also rife.

These are just two examples of many where either Governmental orders or health fears have prevented the well-oiled supply chain from operating as efficiently as has been taken for granted over many years. It’s not so easy to transport wheat around the globe right now…

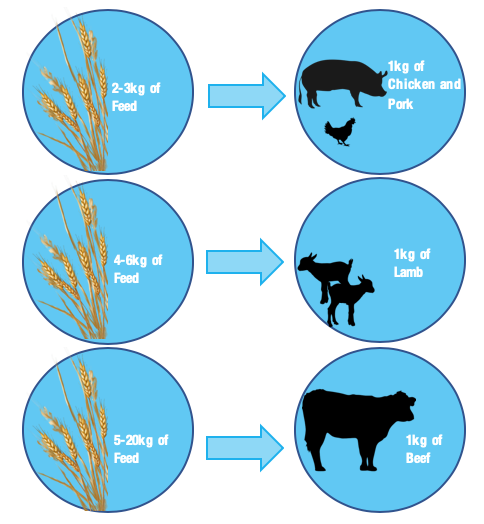

Financial Concerns: As populations have become wealthier over the last few decades, their eating habits have changed. The Western diet has evolved, with many wanting to consume more meat than was done so formerly. The coronavirus has brought out mass financial worry and the macro-economic problems potentially result in a return to more basic food consumption, with meat taking a hit.

Note the amount of feed it takes to produce to following…

So, What Does All This Mean for the Wheat Market?

- Wheat prices have had a turbulent time in 2020 and it may not be over yet.

- As economies get back to work and restaurants reopen, things may appear to get back to more of a normality. However, ongoing workplace constraints and peoples’ financial concerns will linger far longer.

- Coronavirus and its associated issues will live on in memories for many decades to come. The true impact will become evident over time, not in 2020. The financial change and impact on eating habits should not be underestimated.

- It is nonetheless clear to see there are many concerns, from peoples’ jobs and their ability to feed themselves and their families, to Governments concerned for the very infrastructure within their countries.

- This is likely to impact on the wheat market throughout 2020 and well beyond.