Insight Focus

- Russia-induced grains shortages could prompt instability in the Middle East and Africa.

- Countries must secure grains supply from alternative sources.

- India and Turkey are crucial to the continued supply of grains.

The food security of some of the world’s most vulnerable countries has been the collateral damage of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Middle East and Africa are highly dependent on Black Sea grains, but now the tide is turning. With record wheat stockpiles, India could hold a competitive advantage over other potential suppliers.

Middle East Bears Brunt of Grains Disruption

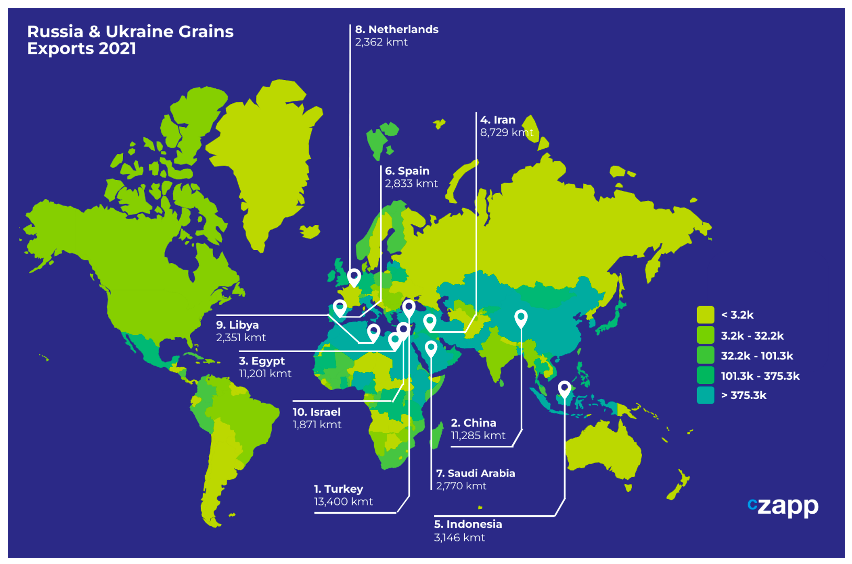

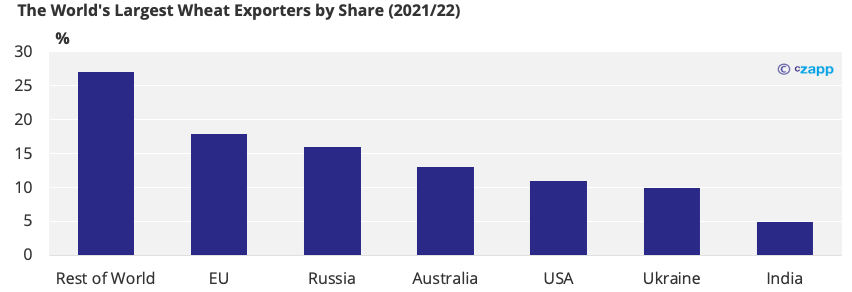

The disruption to Russian and Ukrainian grains trade has implications for the entire global supply chain. According to the International Grains Council, the world consumes 2.3b tonnes of grains each year. Russia and Ukraine collectively produce around 200m tonnes of this, accounting for 9% of global supply.

While this is a global issue, it impacts some regions with greater intensity than others. Many of the most impacted areas are in the Middle Eastand Africa – regions that generally experience high levels of food insecurity.

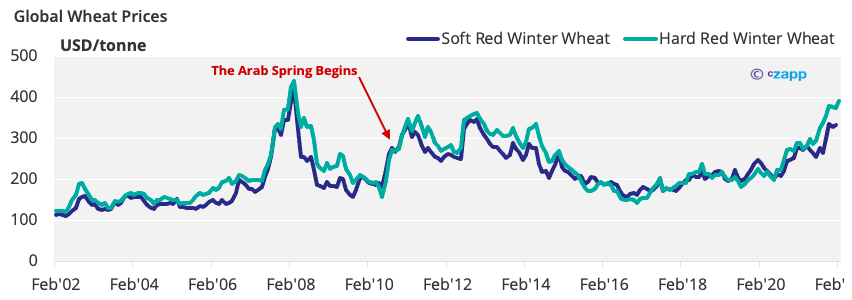

As global food prices continue to rise, an increase in the cost of staples such as wheat could prove problematic for countries in the Middle East. The last time wheat prices rose as sharply as they have over the past year was in the immediate run up to the Arab Spring protests.

Rising food prices and unaffordable living costs are hardly the ideal situations for governments, especially those who endured the previous uprising.

Egypt Cancels Tenders as Prices Soar

Egypt is highly exposed to Russian and Ukrainian grains trade. It produces just 9m tonnes of wheat per year but is the largest per capita consumer of bread in the world. This means wheat consumption for 2021/22 is estimated at 21.3m tonnes.

After one failed tender that was cancelled on the 24th February, Egypt launched a subsequent tender on the 26th for 55k tonne and 60k tonne cargoes of wheat for delivery mid-to-end-April. The General Authority for Supply Commodities (GASC) later announced that both tenders had been cancelled amid very low participation rates. The GASC has not launched any further tenders and the government’s current wheat reserves are currently large enough to satisfy about four and a half months of supply.

There are only 14 countries that are approved to sell wheat to Egypt, including Russia and Ukraine.

Wheat from Kazakhstan will also be accepted depending on specifications. This is because the moisture limit for Egyptian wheat imports is normally set at 13%, but this will be raised to 13.5% to enable new supply.

But as other countries look to shore up wheat supply because of exposure to Russia and Ukraine, Egypt still may struggle to plug the holes. Both Romania and Hungary have announced a ban on wheat exports, while Bulgaria has announced plans to bolster reserves, leading many to fear an imminent export ban. Serbia, however, has said that it won’t ban exports and doesn’t expect a supply issue. Egypt has also imposed a three-month ban on cooking oil, corn, and green wheat exports.

Turkey Shields Wheat Flour Supply

Turkey is another country that may feel the pinch of fewer wheat exports from Russia and Ukraine. Situated on the other edge of the Black Sea, Turkey is normally the recipient of wheat shipped across the Black Sea from Russia and Ukraine on coasters, but lower imports last year prompted the USDA to predict a tightening in stocks.

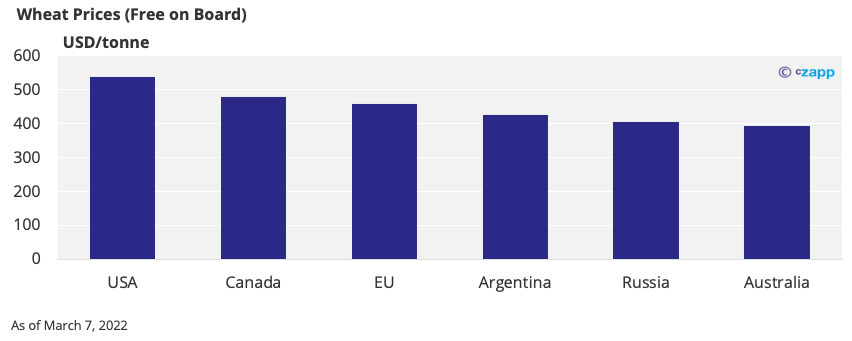

According to the USDA, a successful tender in January meant Turkey was able to purchase wheat at prices of around 341-351 USD/tonne in January. But by March, prices had reached 409-517 USD/tonne, causing Turkey to pull back from large purchases.

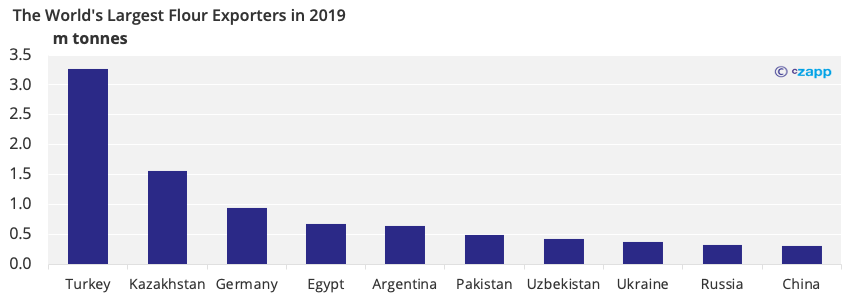

Another implication of tight grain supply in Turkey is its status as a re-export supplier to low-income countries in the Middle East. More than 30% of Turkey’s wheat flour and pasta products are sold to Iraq. Yemen and Syria are also major export destinations. Yemen is largely dependent on food aid for its

flour, while Syria is a close ally of Russia and could potentially access Russian wheat.

Kazakhstan is also a major wheat flour exporter. But like Turkey, it’s not a major wheat producer, harvesting just 12.5m tonnes per year. Also, like Turkey, Kazakhstan sources much of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine. The next option for Iraq would be to source wheat flour from Europe, but it would be difficult to fill the absence of over 3m tonnes of Turkish flour.

Although there’s been no impact on wheat flour yet, the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry added wheat products to its list of items eligible for export regulation on the 4th March. This indicates that Turkey will likely cut off these exports if domestic supply is compromised.

Where is All the Grain?

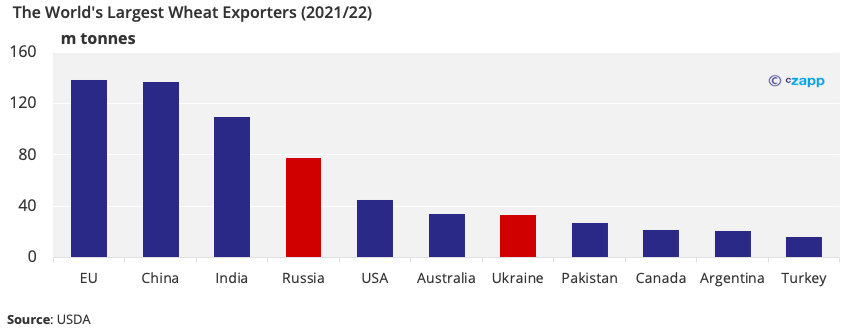

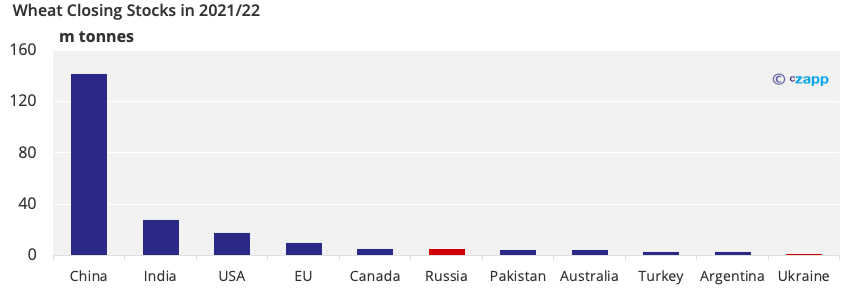

Ukraine and Russia are two of the world’s largest grains producers, but if we eliminate them from the supply chain, what are the alternatives? China and India are the largest grain producing countries, but neither export much. China is by far a net importer of wheat, while India exported just 5m tonnes of wheat in 2021/22.

However, India did increase its exports last year in response to competitive global prices and constrained Black Sea supply, so there’s no reason why India would not speculatively plug some of the gaps in Black Sea supply, bolstered by its sizeable stockpiles. As of November, Indian wheat stocks were at a record 27.8m tonnes, over three times more than required.

The Indian government is reportedly scrambling to ensure it has the infrastructure in place to ensure competitive wheat exports. Extra rail wagons are being made available and the government is working with port authorities toensure priority is given to wheat exports. The government is also recruiting over 200 laboratories to test the wheat quality. There have been contracts signed for about 500k tonnes of Indian wheat exports in the past week, according to reports by The Times of India.

Aside from India, Australia is one of the next largest wheat exporters. Australia has experienced a second strong year in wheat production with production set to hit 34m tonnes in 2021/22.

However, freight from Australia will likely drive prices up, while India very much has the competitive advantage. Australia also has very low stockpiles compared to India, meaning it may be less willing to export in high volumes amid a potential wheat shortage. India buys wheat from local farmers to support incomes.

Canada has already been urged to open its silos to tackle the issue. However, the country is hesitant to do so given a poor harvest resulting from drought and reduced planting area. This meant Canada’s 2021 wheat production was down 38% year on year.

India Among Most Competitive Options

Wheat prices vary greatly, but at the moment, India is an extremely attractive option. While most global exporters are offering at over 400 USD/tonne, Indian contracts have been signed at prices between 305 to 350 USD, according to a report by The Times of India.

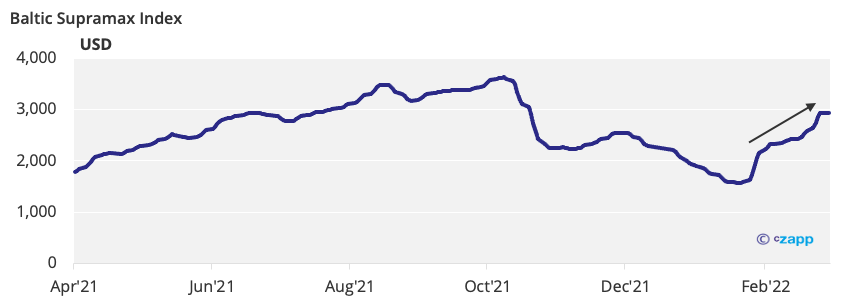

These prices do not include freight, which is also an area where India has a strategic advantage. India can easily access the Middle East and North and West Africa with very competitive freight costs. Buying from Australia, for example, would incur far higher costs, meaning the price for delivered wheat would be far more competitive than any other option, especially amid rising freight prices.

Concluding Thoughts

- The war in Ukraine may jeopardise Middle Eastern food security as wheat prices rise at rates not seen since the lead up to the Arab Spring in late 2010.

- Several countries are now limiting or banning wheat and wheat-product exports to guarantee their own supply.

- Storage capacity is limited to a handful of countries, which makes other countries vulnerable to price volatility.

- India, with about 42m tonnes in its stockpiles, could step in to shore up the Middle East if prices are favourable.

- Grain exporters and traders and now highly susceptible to Turkish and Indian government policy.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Russia & Ukraine Grain Flows Likely to Be Disrupted into H2’22

Russia Sanctions Weigh on Agri Trade Flows

Explainers That May Be of Interest…