Insight Focus

- Many offset buyers prefer to do their own due diligence.

- This is because of the reputational risk of being associated with offset projects.

- Carbon credit rating agencies have emerged to help buyers.

Carbon offset survey highlights continuing importance of buyer due diligence.

Efforts to standardise and streamline the carbon offset market, including initiatives aimed at providing greater transparency into the quality and reliability of credits, have yet to make a significant dent in buyers’ desire to carry out their own due diligence on the integrity of offsets before purchasing, a survey has found.

Since carbon credit projects cover a wide array of technologies, geographies and scale, analysing and comparing them is relatively labour-intensive work that often requires specialist knowledge. Equally, the carbon credit sector has been dogged by allegations of faulty calculations, overestimation of carbon reductions and even human rights abuses.

The main concern for many buyers is the reputational risk of being associated with projects that are found not to be reducing as many emissions as claimed, or that are implicated in legal infringements. Given that the practice of offsetting is frequently attacked as not helping to reduce emissions, but instead simply allowing emissions to be emitted elsewhere, buyers are naturally alert to any risks.

The past several years have seen the emergence of carbon credit rating agencies, who investigate projects to ensure they are delivering real, additional and verifiable emission reductions. Companies such as Sylvera, BeZero and Pachama have developed expertise in calculating the effectiveness of carbon credits in achieving their ultimate goal – reducing CO2 emissions.

“There is a strong need for comparability across projects, even more so across standards, and rating agencies are the only groups offering that service,” the study pointed out, though it added that “companies are hesitant to trust agencies’ secondhand analyses over the verified work of the project developers. Our sense is that rating agencies will need thorough peer review before they gain full credibility in the market,” the Nature Conservancy said.

The study found that the majority of participants prefer to carry out their own in-house due diligence on the quality of offsets available to them, resorting to outside carbon credit rating agencies mainly “to manage reputational risk and fill information gaps.”

This due diligence process can take anywhere from a few weeks to several months to carry out, the survey found.

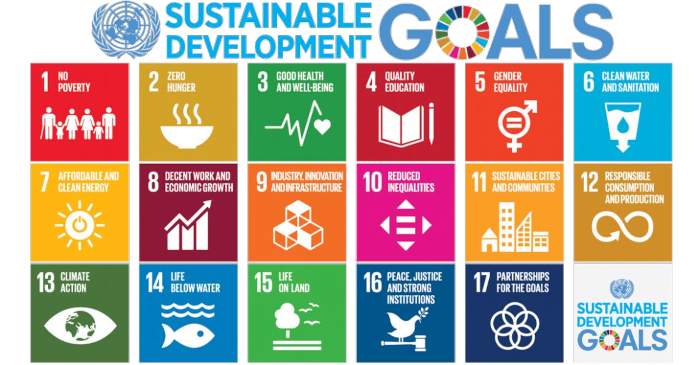

Some buyers choose to issue tenders for carbon credits, specifying in advance the project type, standard and even a set of preferred co-benefits (usually related to UN Sustainable Development Goals).

Pre-qualified credits are then subjected to analysis covering elements such as permanence, additionally and, most commonly, political, counterparty and reputational risk, the study found.

“Participants emphasised the importance of looking project-by-project (55%), methodology-by-methodology (22%), or both (22%) rather than standard-by-standard,” the report stated.

“Standards certainly can give some indication of quality, but no credits should be purchased based on that attribute alone. “One respondent noted that the methodology reveals the quality of carbon accounting, but social and biodiversity benefits are always specific to the project.”

The report found that buyers use a variety of public information sources to research projects and counterparties, including media coverage and government information, as well as rating agencies’ output. The largest investors may also carry out site visits to specific projects to satisfy themselves of the credits’ quality.

The survey found that appropriate baselines, additionality, and permanence were the most important criteria in selecting credits. There has been some controversy in recent months surrounding a number of projects that are alleged to have set the baselines from which they calculate emissions reductions too low, leading to inflated claims of reductions.

Additionality has also long been a source of criticism. Projects are said to be “additional” if the carbon finance they attract is the main factor in the project going ahead. Emerging technologies such as renewable energy are no longer “additional” in many parts of the world as the technology can now compete with legacy technologies such as gas or coal without any financial assistance.

Permanence is also a concern for many buyers. Many nature-based project types such as avoided deforestation can suffer from reversals due to fire, disease or illegal harvesting. Many standards now require certain nature-based projects to deposit a portion of their credits in “buffer” accounts, to be retired in the event of any adverse events.

In addition, carbon credit projects are also often judged according to the non-carbon benefits they can bring. These range from preserving local biodiversity to generating economic opportunities for local communities. Certain standards offer certification that highlights some, but not necessarily all of these so-called co-benefits and so further research may be needed to identify them.

The poll was carried out by the Nature Conservancy, a US-based non-profit, among 24 stakeholders covering buyers, investors and sellers.

Source: United Nations