Insight Focus

- After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, there as panic in grains markets.

- There was speculation that restrictions on Ukrainian grains could exacerbate food inflation.

- Now after two years, how has Ukraine adapted to the new landscape?

War Limits Grains Exports

With Russia’s shock invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, there was widespread concern over the global supply of grains. Known as the breadbasket of Europe, Ukraine was responsible for 8% of global grain exports. Russia was also a formidable exporter – the number one globally.

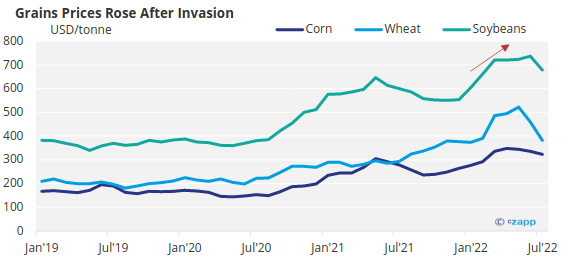

Of course, the invasion sent shockwaves through the grains markets and concerns about restricted supply caused prices to jump in the second quarter of 2022.

Source: World Bank

Since then, two years have passed and there have been some definite changes. So, how exactly has global grains trade changed due to the war in Ukraine?

Grains Trade Lower but Continues Recovering

As expected, at the beginning of the invasion, almost no grains were able to leave Ukraine. Established trade routes were concentrated in the Black Sea and it was just too risky for many shippers to enter the ports out of fear of Russian attacks.

Later though, the Black Sea Grain Initiative was set up via the United Nations and Turkiye. This allowed grains exports to resume from three key Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea – Odesa, Chornomorsk and Yuzhny/Pivdennyi – to the rest of the world. Despite the agreement falling apart in July 2023, Ukraine was still able to export grains via the Black Sea thanks to military protection.

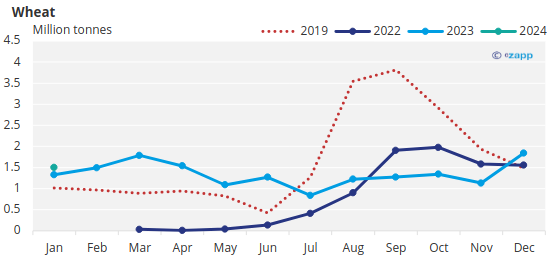

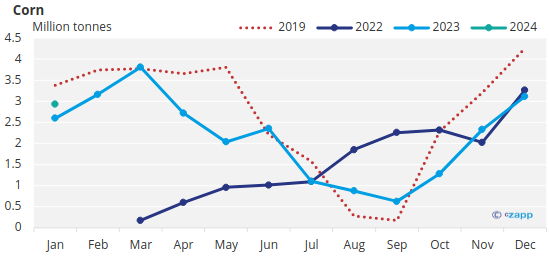

Source: Ukraine Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food, UN Comtrade

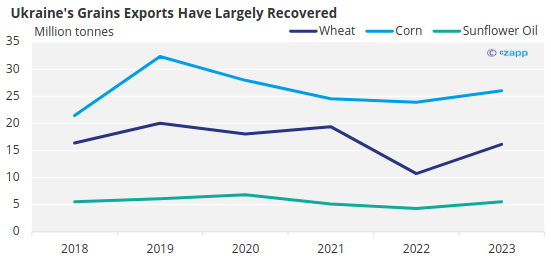

As a result, exports of grains from Ukraine have continued to recover. While they’re still not quite at pre-war levels, Ukraine has managed to export impressively large amounts of grains in the past two years. Export volumes do remain volatile though.

Source: UN Comtrade, Ukraine Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food

Price Impacts Become Limited

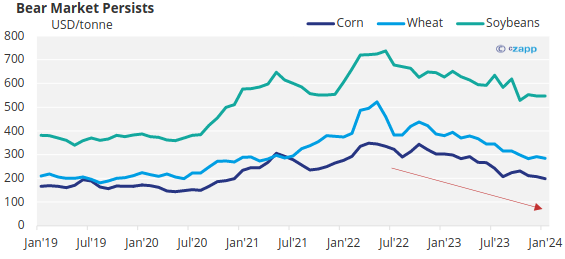

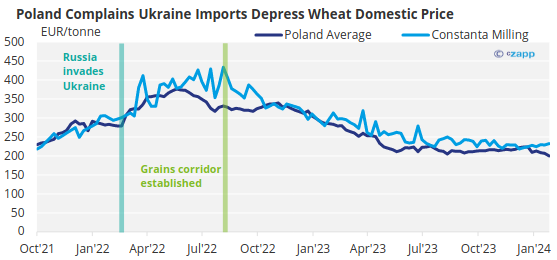

The prices of grains rose substantially when the war broke out. However, since the grains corridor was set up, prices largely receded and, for the rest of 2022 and 2023, grains have experienced a prolonged bear market.

Source: World Bank

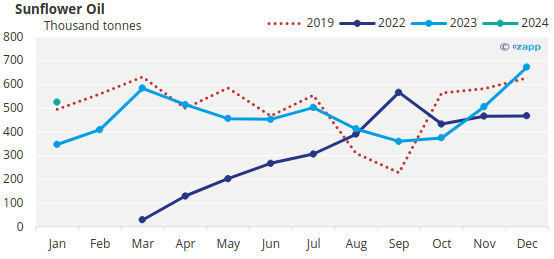

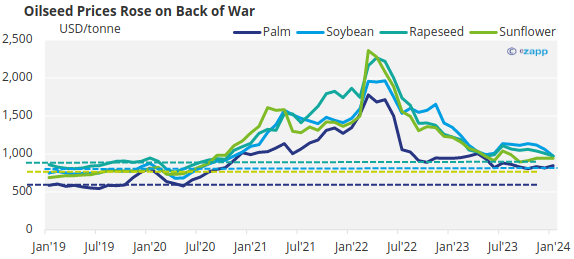

The same can be said for oilseeds. Given that Ukraine is a major sunflower oil producer, there was initial panic when war broke out that extended to a rally in palm oil, soybean oil and rapeseed oil.

Note: Dashed lines indicate 2019 average

Source: World Bank

Prices have now normalised, given that sunflower oil trade from Ukraine has recovered, although they remain slightly above average 2019 levels.

Trade Composition Changes

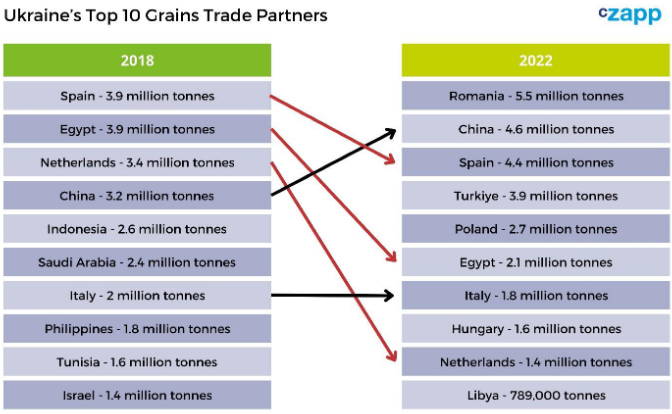

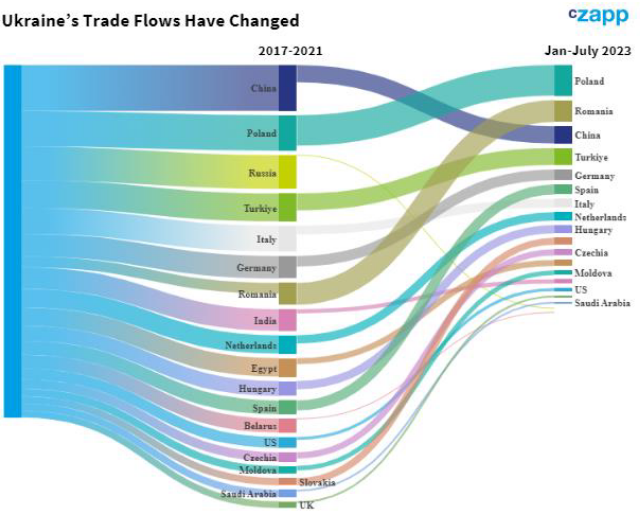

So, if prices are back to normal and exports have more or less recovered, what has actually changed in the past two years? Well, the composition of Ukraine’s largest trading partners has been transformed.

Egypt, for instance, has gone from being Ukraine’s second largest grains export destination to the sixth, while more of the top spots have been taken by European countries due to logistical issues.

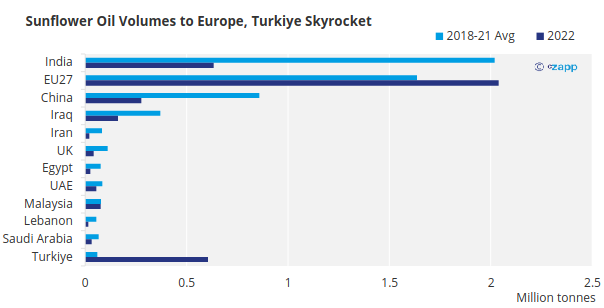

Drilling down into individual products, India has gone from being the largest sunflower oil importer at about 2 million tonnes per year to importing just 633,000 tonnes per year. While Ukrainian sunflower oil exports to the EU have increased, the biggest winner has been Turkiye. The Eurasian country imported over 600,000 tonnes of sunflower oil in 2022 – 10 times more than its 2018 to 2021 average.

Source: UN Comtrade

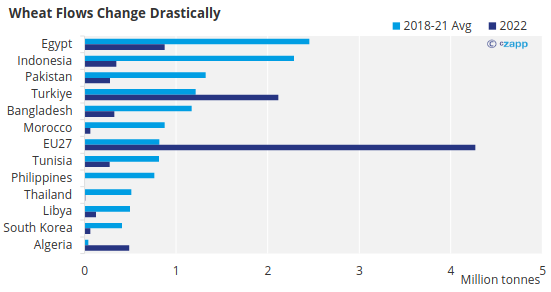

In terms of wheat, the biggest shift has predictably been in favour of the EU. This can be explained by Ukraine’s land bridge solutions, sending wheat to Europe via neighbouring Poland and Romania when Black Sea routes have been blockaded.

EU27 countries imported 4.2 million tonnes of Ukrainian wheat in 2022, compared with just 815,000 tonnes per year between 2018 and 2021. In comparison, flows of Ukrainian wheat to Egypt have more than halved and wheat exports to Indonesia have dropped by more than six times.

Source: UN Comtrade

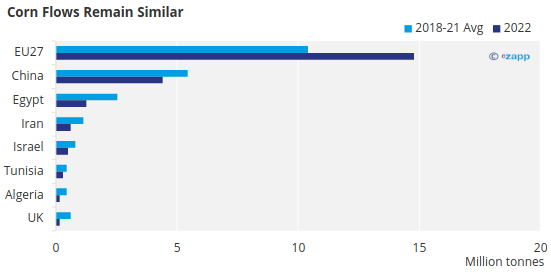

But trade in corn has remained similar to before the war. EU27 countries are now importing more Ukrainian corn but they have always been the largest recipient. Exports of Ukrainian corn to China, Egypt and Iran have dropped marginally.

Source: UN Comtrade

New Flows Distort Markets?

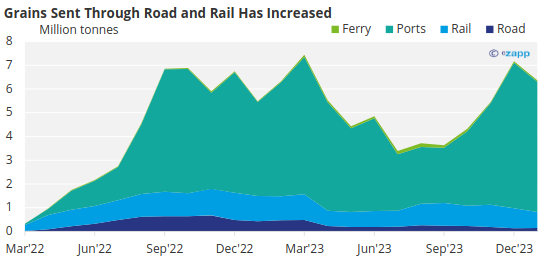

Another change is in the composition of grain trade routes. As mentioned, the Black Sea has not always been open for Ukrainian grains due to Russian blockades. This means Ukraine had to re-route some cargoes via road and rail.

As Black Sea routes re-opened, some grains were still sent through alternative methods. There are still around 1 million tonnes of grains sent through road and rail each month, although this has declined in recent months due partly to protests in Europe.

Source: Ukraine Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food

Poland has now become Ukraine’s largest trade partner, followed by Romania.

Source: Informall Business Group

Polish farmers have complained that this is creating a price distortion in European wheat prices. Polish farmers argue that the large volumes of wheat imported from Ukraine are depressing prices that can be obtained by Polish farmers.

Source: European Commission

What Should We Expect?

- Despite the challenges of war, Ukraine’s grains trade has remained remarkably resilient.

- The ability to pivot quickly means that trade volumes are recovering, and elevated prices are normalising.

- But grains flows have certainly changed, and some low-income countries have lost out.

- Challenges remain as some European countries are becoming reluctant to accept more Ukrainian grains citing price distortions.

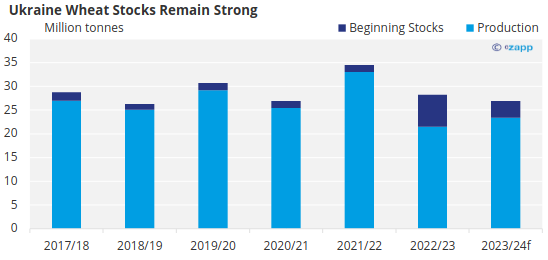

- One of the biggest question marks in 2022 was over the condition of Ukraine’s future crops given the impact of warfare on the land.

- However, USDA figures show that Ukrainian wheat production is set to remain strong in the coming year.

Source: USDA