Insight Focus

- Panama Canal water levels are still critically low.

- Alternatives such as land bridges and diversions are available.

- However, costs and disruption are likely to stay high until heavier rainfall around October.

Gatun Levels Sink

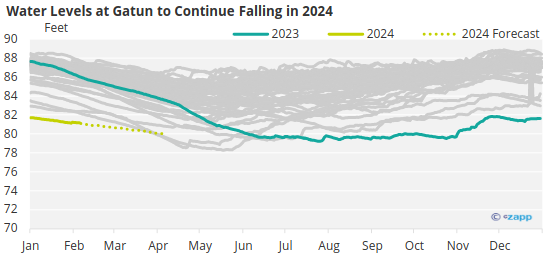

Water levels at Gatun Lake – the main body of water that feeds the Panama Canal – are continuing to dwindle. As of the latest forecast, levels are at around 81 feet and are expected to fall more in the coming months – to as low as 80 feet in April.

Source: Panama Canal Authority

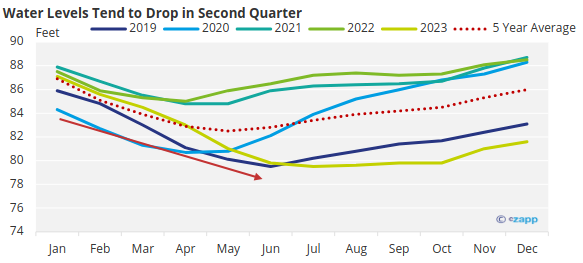

Due to the seasonality of rainfall, the Canal water levels normally decline during the second quarter. The rainy season normally begins in May and lasts until December, bringing high rainfall that replenishes the Canal.

Source: Panama Canal Authority

But in the rainy months of 2023, rainfall fell well short of the five-year average, meaning Gatun entered the dry season with lower-than-normal water levels. This was exacerbated by the fact that El Nino began, which tends to result in reduced rainfall around the Pacific.

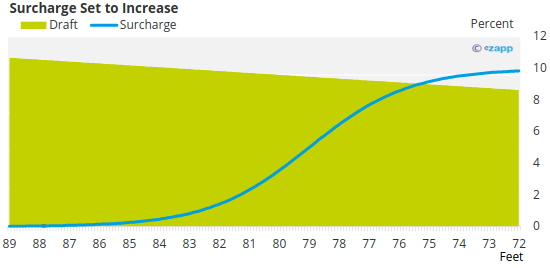

Drafts Fall, Surcharges Rise

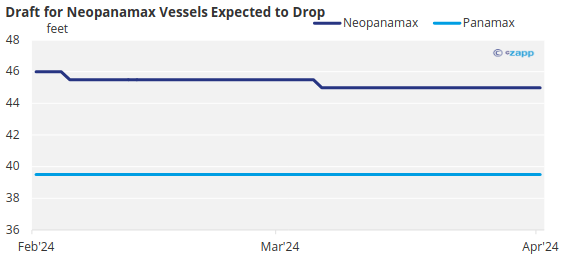

This is adding extra pressure on ships to reduce their drafts in order to cross the Canal. In the Neopanamax locks, the maximum draft is now at 46 feet and the Panama Canal Authority expects to make two more cuts in the coming months.

Source: Panama Canal Authority

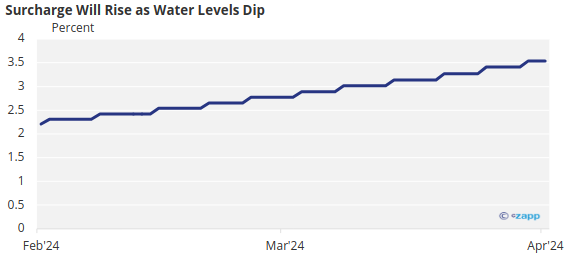

As a result, the surcharge for using the Canal will increase. At a total draft of 85.5 feet, the surcharge has now reached 2.21%. Current projections by the Panama Canal Authority place the surcharge at 3.5% as of April.

Source: Panama Canal Authority

If the draft falls as low as 72 feet, the surcharge could rise as high as 9.85%.

Source: Panama Canal Authority

Alternative Options Needed

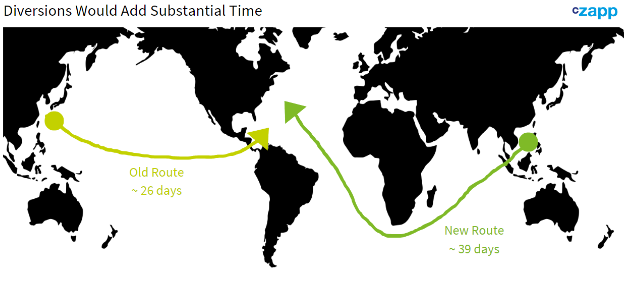

Due to the increased cost associated with transiting the Panama Canal, shipping liners are now looking at alternatives. The obvious next option would be to re-route ships. However, this would add substantial time and cost to voyages.

Ships travelling from Asia to the US East Coast could travel around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa instead of across the Pacific and through the Panama Canal. However, this route would add 13 days to journeys, especially since the Suez Canal is also mostly off-limits thanks to Red Sea conflict.

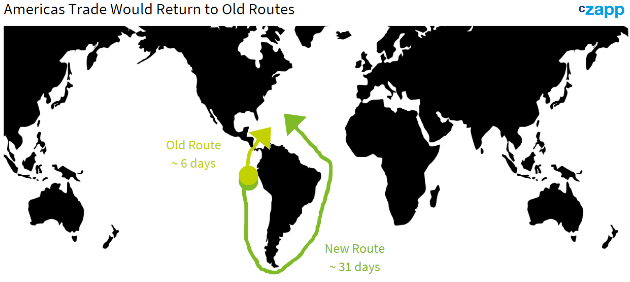

And for those that want to send goods from West Coast South America to North America, they would need to return to old trade routes used prior to the Panama Canal being built. This would add an estimated 25 days to voyages.

Rail Solutions Could Alleviate Blockages

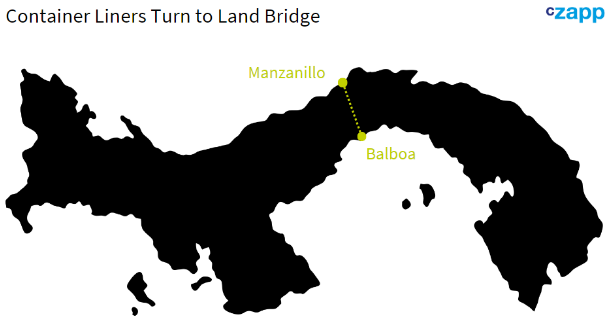

One other alternative for companies is to use a land bridge. Already, Maersk has announced it would use a land bridge for its OC1 service, whereby the cargo would be unloaded at the port in Panama, and sent across Panama by rail to reach the opposite coast.

According to reports, this land bridge will have two loops – one for Atlantic trade and one for Pacific. Goods crossing the Pacific will be unloaded at the Canal entry in Balboa and sent by train across the land to reach another ship in Manzanillo that will take them to North and Latin America.

At the same time, goods sent via the Atlantic will be unloaded at Manzanillo and sent in the opposite direction for onward transit to the Pacific. This option will of course add time and costs to transits.

Mexico is also stepping in by reopening its Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The project has set out to revive several kilometres of old railway tracks to move passengers and goods from the state of Oaxaca on the Pacific coast to Veracruz on the Atlantic.

The service was used in the late 1800s and early 1900s but was largely forgotten after the opening of the Panama Canal. Now, Mexico’s President wants to capitalise on disruption at the Canal. The revamped route was inaugurated in December.

Concluding Thoughts

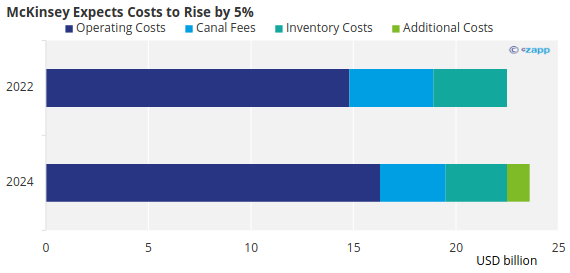

Regardless of short-term solutions, the Panama Canal has always been the most efficient way to transport goods through the Americas, and any disruption will lead to a price increase. According to an analysis by McKinsey, the situation will lead to cost increases of 5% — or about USD 1.1 billion.

Source: McKinsey

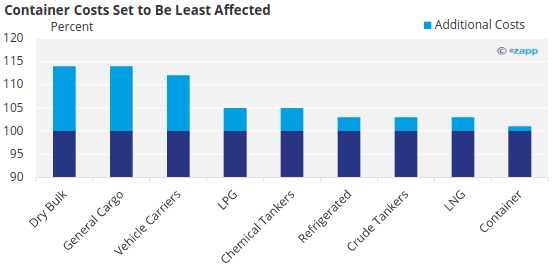

The silver lining is that containers are set to be the least affected – although they will still experience price increases.

Source: McKinsey

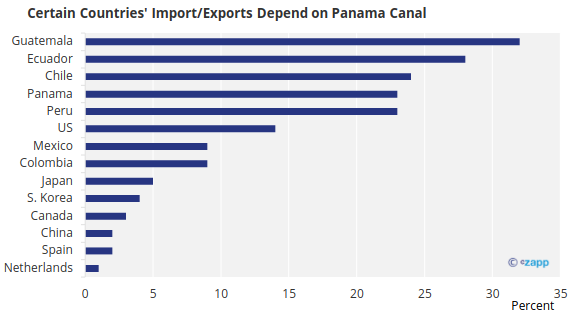

Not only will direct prices of shipping increase, but the cost of goods will also rise due to the huge concentration of trade that runs through the Canal every year. Delays will lead to higher prices being passed on to consumers, as well as higher risk of spoilage for agricultural goods.

Source: McKinsey

But there may be light at the end of the tunnel. According to an analysis by Panama’s Institute of Hydrology and Meteorology (IMHPA), the rainfall deficit tends to be more pronounced during the first year of the El Nino phenomenon. Normally, El Nino is finishing by the middle of the second year, and so excess rainfall in the second half of the second year tends to mask low rainfall in the first 18 months.

Given that the current El Nino is estimated to have started in April 2023, we should expect to see continued low rainfall impacting Canal water levels until at least October. At this point, the drought should start to alleviate.