Insight Focus

- Ukraine is world’s fifth-largest grains exporter, Russia the first.

- Ukrainian ports, railways paralysed by conflict.

- Trade activity could take months to normalise.

Ukraine’s grain exports accounted for 8% of the global total in 2020 (USD 3.6 billion). Commercial trading through ports has been suspended amid the recent Russian invasion and trade lines have been disrupted. This will likely have long-term implications for the grains industry, particularly in Middle Eastern countries that rely primarily on Ukrainian grains.

Grains Shipping Disrupted

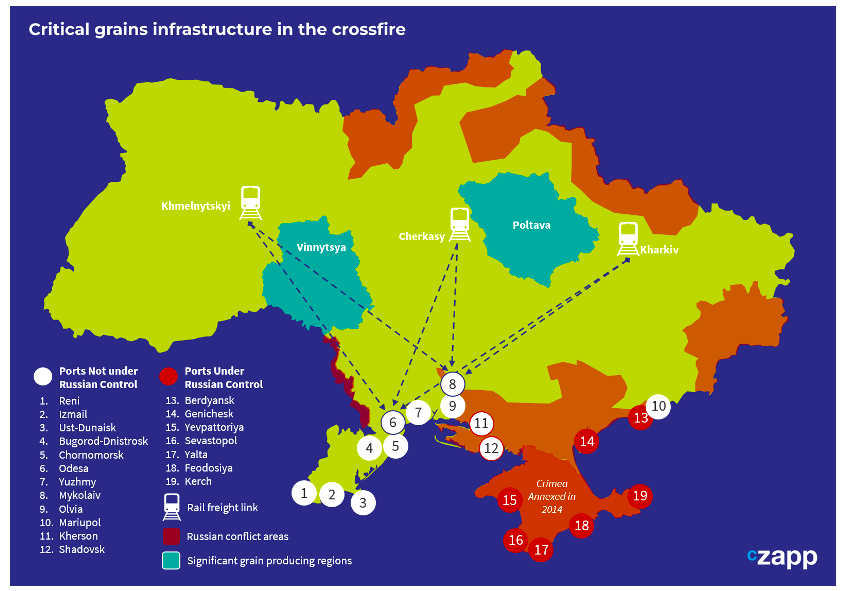

All Ukrainian ports have now been closed after the country declared a state of emergency upon invasion by Russia last week. Railroads across the country have also been destroyed due to the conflict. The invasion has huge implications for the global grains trade as about a quarter of the world’s grains are supplied by Russia and Ukraine.

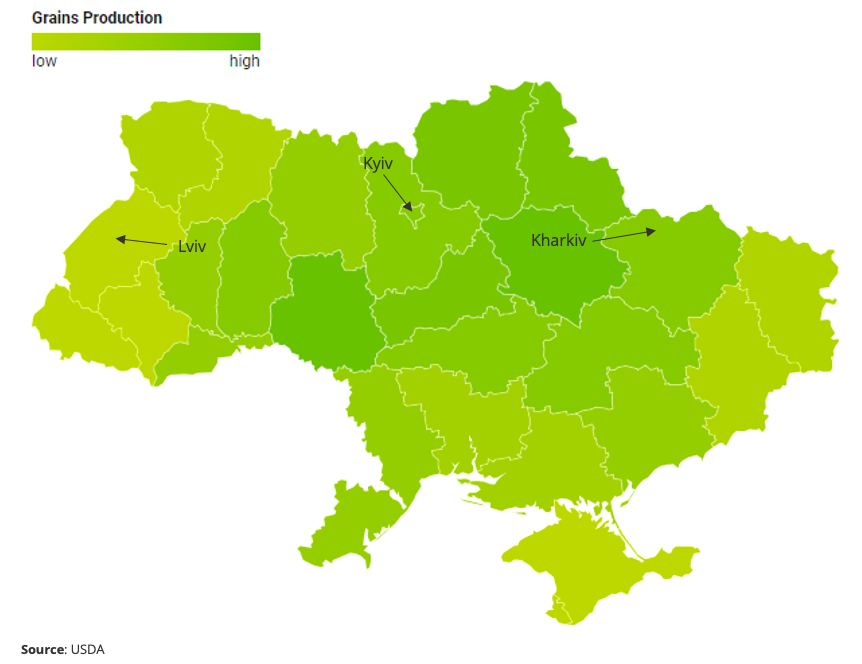

Ukraine’s primary grain-producing regions have not yet been reached by Russian forces, which are still clustered on the borders and in the cities of Kyiv and Kharviv. The country’s main grain-producing regions are Vinnytsia and Poltava in the centre of the country.

Ports Closed for Business

The Russian invasion is taking place on three fronts: from Crimea in the south, Russia and Donbas in the east, and Belarus in the north. According to the Financial Times, Russian forces have taken much of the Black Sea region, including the port of Berdyansk.

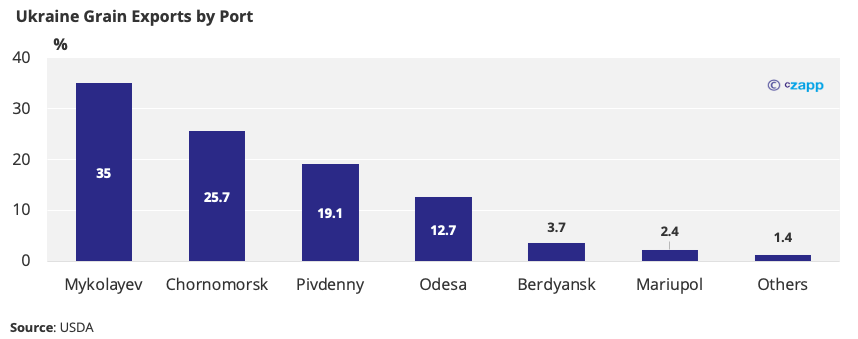

Forces have also surrounded the port of Mariupol in the Donbas region, a critical port for metals, mining, and oil. The port alongside Berdyansk handles about 6% of the country’s grain exports. As it lies just 10km from separatist strongholds, Russian forces quickly targeted the city and its port.

Most of Ukraine’s grains (about 93%) are shipped via four Black Sea ports in southern Ukraine: Odesa, Pivdennyi, Mykolayiv and Chornomorsk.

Ukraine Declares a State of Emergency

The ramifications of the state of emergency will be felt far beyond the Ukrainian ports.

About 68% of Ukraine’s grain moves by rail, but with around 100,000 refugees having crossed the border in the first few days of the conflict, railway lines will likely be paralysed. Several other states have offered more train cars for evacuation, tying up railway lines used for freight. Ukrainian Railways is currently operating in emergency mode.

Coupled with this is the current conflict area in Kyiv as Russian forces attempt to take the capital. Most rail routes in Ukraine run through the city. Now, the fighting has destroyed railway infrastructure across the country.

“Railroad crossings between countries that used to transport thousands of goods and bring millions of dollars to the economies of both countries have been destroyed,” Ukrzaliznytsia, Ukraine’s state railway company, said in a post on the Telegram social media platform.

What Does This Mean for Grains?

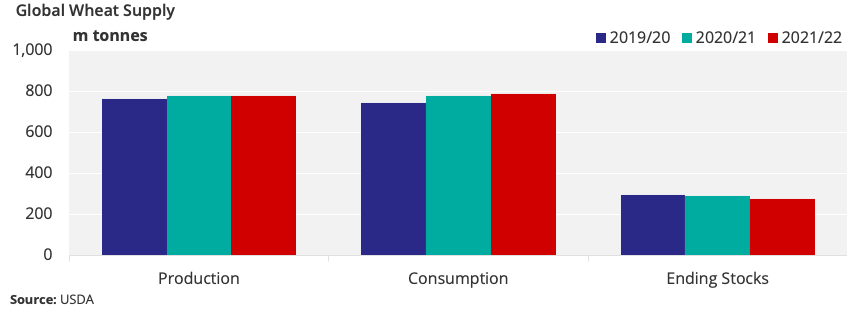

Global wheat stocks have been declining since 2019 as consumption increases and production plateaus.

Ukraine supplies a significant amount of grain to several Middle Eastern and European countries. In 2021, the largest importer was China, followed by Egypt.

The Middle East & North African region (MENA) is particularly exposed to grain imports from Ukraine. Egypt imported a massive 5.5m tonnes of grain from Ukraine in 2021, accounting for almost 25% of Egypt’s total grain imports. Likewise, Israel imports about 1.7m tonnes per year, 1.2m tonnes of which comes from Ukraine. As well as MENA, several European countries are also exposed to grains shortages if Ukrainian supply chain disruption continues.

Potential risk for grains exporters intensifies as traders seek to avoid conflict zones. There have already been reports of commercial ships being caught in the crossfire of the conflict.

Russian grain exports are concentrated across a handful of countries, with almost 70% going to the top 10 countries. Supply to neighbouring countries, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, won’t likely be disrupted, but further conflict in the Black Sea could harm MENA supply.

It’s worth noting that the second half of the year is much more important for grain flows. Around 3.6m tonnes of wheat is exported in August, with a further 4.5m tonnes exported in September. Whilst the first half of the year is not quite as crucial for grains shipments, the volumes involved should still cause disruption across the supply chains. These disruptions will be exacerbated if the conflict continues into summer and beyond.

Concluding Thoughts

- Russia’s invasion is a cause for concern across the global grains supply chain.

- The MENA region will likely experience the greatest disruption.

- With railway lines destroyed, Ukrainian grains trade is unlikely to get back on track any time soon.

- The world should therefore prepare for grains shortages stemming from the conflict.

- The duration of the disruption will likely extend into at least the second half of the year.

- If the conflict lingers, grains exporters will likely seek alternative long-term strategies.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…