Cross-commodity spread trading, exemplified in the dairy industry, involves the simultaneous purchase of one commodity and the sale of another. This strategy is commonly executed using commodity derivatives markets, particularly futures, to manage risk and capitalize on price differentials. In the dairy sector, this approach can be applied to products like skimmed milk powder (SMP), presenting both risks and opportunities. The degree of correlation between the involved assets is crucial to the effectiveness of this strategy, as it can significantly impact risk exposure and potential returns

Definition of correlation: a mutual relationship or connection between two or more things.

Definition of basis hedge: using risk management tools for a given product to reduce the price risk of a similar product which is deemed to be related.

What is a Cross-Commodity Spread Trade?

Sometimes two seemingly similar goods can be trading at materially different prices. This might not make sense to you. If that is the case, you should investigate whether a Cross-Commodity Spread trade could be likely to yield a profit.

For example, skimmed milk powder might be trading in Europe at $2,000 USD/MT equivalent and trading in New Zealand at $3,000 USD/MT.

If this opportunity were present, a trader would seek to profit from this by buying the cheaper European price and simultaneously selling the more expensive New Zealand price.

The derivatives market can be used to execute both trades. It is a basis trade.

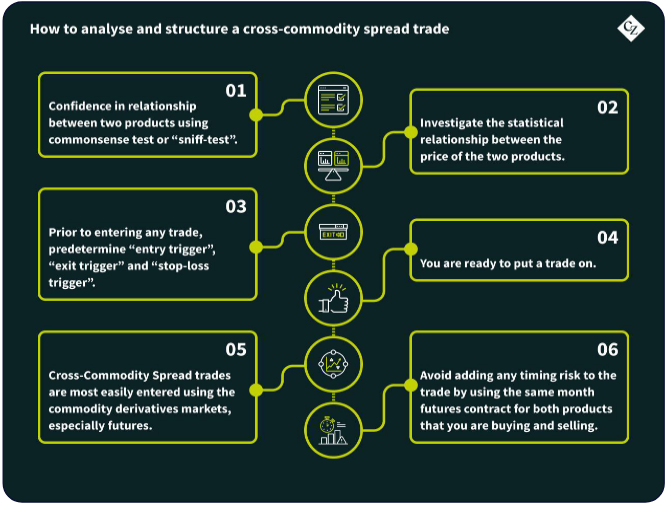

How to analyse and then structure a typical Cross-Commodity Spread Trade:

Firstly, you want to be confident that there is actually a relationship between the two products. A commonsense test (or “sniff-test”) is the best starting point for this.

If the products seem like genuine substitutes to you then you should investigate the statistical relationship between the price of the two products, especially the correlation between their prices (and the changes in their prices).

If the price of the products exhibits a strong correlation (a good rule of thumb is that this should be higher than 0.70) you should then look at the statistical distribution of the spread between these price series, especially for any skew and seasonality. You should then determine some percentile which you would be confident that prices had diverged enough for there to be a trading opportunity, i.e. your “entry trigger”. Prior to entering any trade you should also predetermine your “exit trigger” which should be at a level which you would consider pricing to have converged enough to be considered at a normal level. You should also establish a “stop-loss trigger”, that being a point which you cut your losses because the spread has continued to diverge and thus you have reason to believe that the spread may have “broken down” at this point in time.

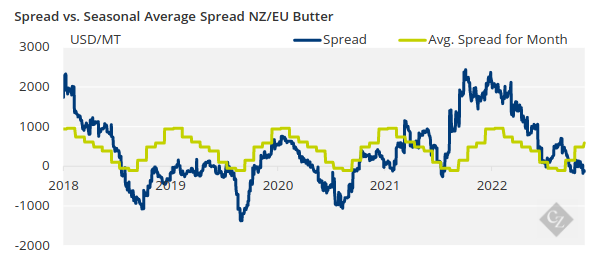

Important factors to consider in setting your trigger levels are (a) the extreme levels of the spread which have previously been reached, (b) how long the spread usually stays open for once the price levels have diverged, (c) any seasonality in the spread itself (which can be driven either by seasonality in the underlying products or in some cases the spread may exhibit an independent seasonality).

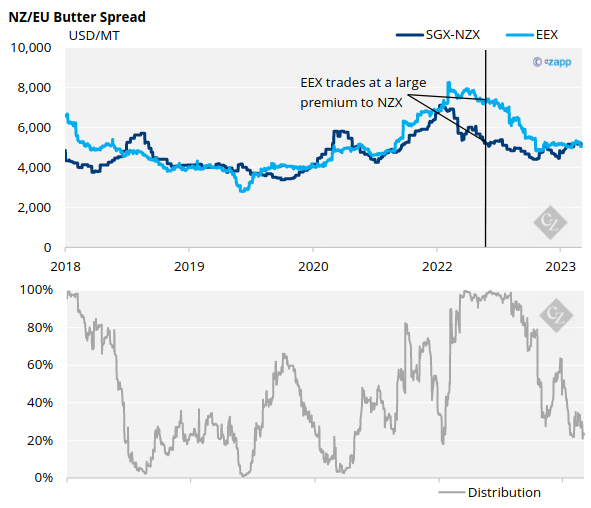

a) See the EEX vs. SGX-NZX Butter below has reached beyond the 1st and 99th percentiles multiple times in the past five years.

b) See the EEX vs. SGX-NZX Butter below usually closes from extreme points within 2 months but at times has remain diverged for over 8 months.

c) See the EEX vs. SGX-NZX Butter spread in the second chart below tends to follow an observed seasonality in in USD/MT. This can help with timing your entry and exit.

If you are now confident that you have two products which are similar enough to exhibit a typical price differential, the spread in prices at present has diverged from this typical differential, and you have a time horizon and triggers to enter and exit the trade at levels where you believe that you are likely to profit, then you are ready to put a trade on.

Cross-Commodity Spread trades are most easily entered using the commodity derivatives markets, especially futures. This is because derivatives markets enable you to trade only the price of products without necessarily owning physical tonnage of that product. Typically, derivatives markets provide the best liquidity to get access to pricing of a product in a transparent manner.

To take purely a cross-commodity spread trade it is important that you do not add any timing risk (also known as calendar risk) to the trade. This is best achieved by ensuring that you use the same month futures contract for both products which you are buying and selling.

Practical benefit Cross-Commodity Spread trades against a physical position:

Aside from outright profit seeking from a perceived mispricing, physical market participants can use this style of trade in an effort to add value to hedge positions.

For example, let’s say a manufacturer who uses SMP as an ingredient has a three year indexed Supply Agreement linked to GDT. GDT SMP can be hedged using SGX-NZX SMP futures, so if the manufacturer saw value in the futures market they could lock this in using the SGX-NZX. However, US NFDM which trades on the CME might be trading at a statistically significant discount to SGX-NZX for the period which the manufacturer wants to hedge. The manufacturer could then buy CME futures instead of SGX-NZX futures for the associated futures month. In doing this, they have given themselves a degree of price certainty plus also the opportunity to profit from the perceived mispricing. The manufacturer has entered into a basis hedge which is likely to enable them to receive physical product at a discount (for those months which the basis hedge is on for).

If you are now confident that you have two products which are similar enough to exhibit a typical price differential, the spread in prices at present has diverged from this typical differential, and you have a time horizon and triggers to enter and exit the trade at levels where you believe that you are likely to profit, then you are ready to put a trade on.

Cross-Commodity Spread trades are most easily entered using the commodity derivatives markets, especially futures. This is because derivatives markets enable you to trade only the price of products without necessarily owning physical tonnage of that product. Typically, derivatives markets provide the best liquidity to get access to pricing of a product in a transparent manner.

To take purely a cross-commodity spread trade it is important that you do not add any timing risk (also known as calendar risk) to the trade. This is best achieved by ensuring that you use the same month futures contract for both products which you are buying and selling.

Practical benefit Cross-Commodity Spread trades against a physical position:

Aside from outright profit seeking from a perceived mispricing, physical market participants can use this style of trade in an effort to add value to hedge positions.

For example, let’s say a manufacturer who uses SMP as an ingredient has a three year indexed Supply Agreement linked to GDT. GDT SMP can be hedged using SGX-NZX SMP futures, so if the manufacturer saw value in the futures market they could lock this in using the SGX-NZX. However, US NFDM which trades on the CME might be trading at a statistically significant discount to SGX-NZX for the period which the manufacturer wants to hedge. The manufacturer could then buy CME futures instead of SGX-NZX futures for the associated futures month. In doing this, they have given themselves a degree of price certainty plus also the opportunity to profit from the perceived mispricing. The manufacturer has entered into a basis hedge which is likely to enable them to receive physical product at a discount (for those months which the basis hedge is on for).

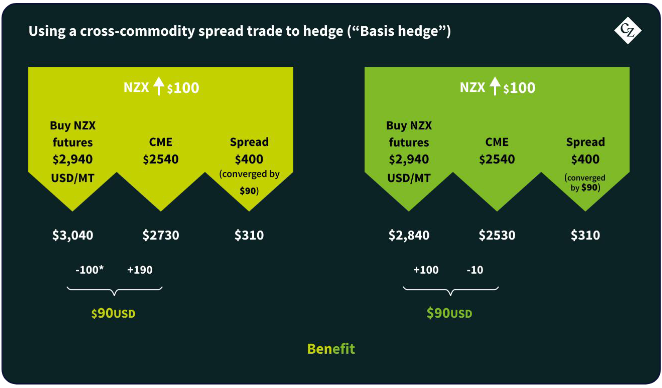

A worked example of using a Cross-Commodity Spread Trade to hedge (“Basis Hedge”):

Let’s say a manufacturer has an indexed Supply Agreement with index “average GDT SMP MH C2 in the month two months prior to shipment + $100 USD/MT”.

The manufacturer wants to lock in their FOB pricing for shipments in Q2-24. They can do this by buying the SGX-NZX futures for an average price of $2,940 USD/MT, thus locking in their FOB pricing for $3,040 USD/MT.

Alternatively, they could use the EEX SMP or CME NFDM futures, which are also for objectively very similar products. For example, CME NFDM and SGX-NZX pricing exhibits >90% correlation.

Their analysts realise that at present the CME NFDM, which is trading at $1.152 c/lb ($2,540 USD/MT) is statistically undervalued vs SGX-NZX. It is important to note here that outright difference is not relevant, it is where the spread is now vs. its average that the analyst should consider.

The recommendation is that CME NFDM should be considered as a basis hedge. The analysis shows that there is likely to be $100 USD/MT of benefit in using the basis hedge and have decided that they are comfortable with 8 months being long enough for the spread to converge.

The recommendation is approved. The manufacturer has their supply chain manager execute the hedge using CME and locks in their Q2-24 pricing.

In March 2024 the SGX-NZX vs. CME spread has converged by $90 USD/MT. The manufacturer is happy to now switch their hedge over to a perfect hedge using the SGX-NZX. They exit the CME position and replace it with an SGX-NZX position.

The cost of having had the basis hedge on is $10 USD/MT more expensive than it would have been to just enter a perfect hedge to begin with.

All told, the manufacturer has netted a $80 USD/MT trading profit from the basis hedge and has essentially reduced the adder on their indexed Supply Agreement from $100 to $20 USD/MT which is significantly more competitive than their baseline.

By replacing the basis hedge with a perfect hedge just before their shipments, they were able to lock in a fixed price of $2,960 USD/MT FOB (vs. the $3,040 that they had considered to begin with).

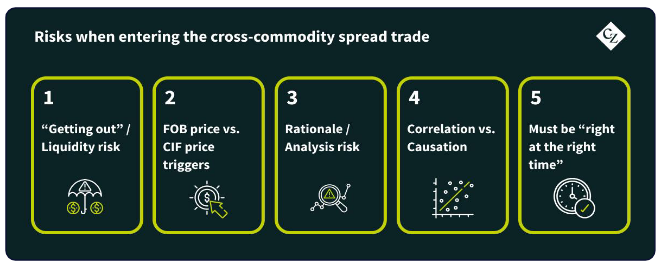

Risks to be aware of when entering the Cross-Commodity Spread Trade:

“Getting out”/liquidity risk: in entering a cross-commodity spread trade, the participant usually has at least one derivative position. When exiting that position there is a risk that the derivatives market does not have the liquidity at the price you would like and to exit you are forced to move the derivatives price against yourself until sufficient liquidity is found. This risk increases with the size of the trade that is on.

FOB price vs. CIF price triggers: Derivatives markets typically trade on FOB terms (or similar) i.e. at origin. While physical sales prices from different origins compete at a CIF term (or similar) i.e. at destination. It is important to understand what is going on in the freight market because this can create FOB pricing dynamics as different origins are forced to compete in destination markets.

Rationale/analysis risk: Humans have an innate self-confidence bias. It is always important to get an independent set of eyes across the detail of your proposal. Ask for feedback and suggested improvements to your model, take these seriously.

Correlation vs. causation: just because the price of two products has been well correlated for some time it does not mean that any structural link exists between them. For example, if butter had exhibited a strong correlation to shares in Toyota for two years would you think that there was a potential spread trade there? At the very least, some comprehensive analysis would be required.

The cost of a spread remaining open longer than you had anticipated: in trading it is important not only to be “right” but to be “right at the right time”. If a spread remains open for longer than anticipated then you need to decide if you roll it or close it. Rolling it involves closing the trade in the existing months and simultaneously re-opening it in deferred months. If the trade has diverged slightly from when you entered (but not beyond your “stop loss trigger”) then you also need to be aware of the cost of funding your margin account for an extended period. This cost can add up and eat away at your potential profit. So too can the cost of rolling the trade, as it involves transaction costs out and then back in for both independent commodities. There is also timing risk when rolling as you need to keep both legs on at the same time, and to do so you may need to cross the spread which increases the overall transaction cost of your roll operation.

Traders do spread trades against your buying all the time…

Want to bring the potential profit of this structure in-house but can’t do it alone? Call us!

To construct a cross-commodity hedge on your own you need:

-

- Access to the associated/appropriate derivatives markets.

- Access to physical product and approval to buy physical product linked to an index.

- The ability to fund potentially large values in your derivative margin accounts for several months.

If you think that this kind of structure could benefit your business but don’t have all of the components in-house, then CZ can help facilitate this for you transparently.

Get in touch with Tom at TSoutter@czarnikow.com.